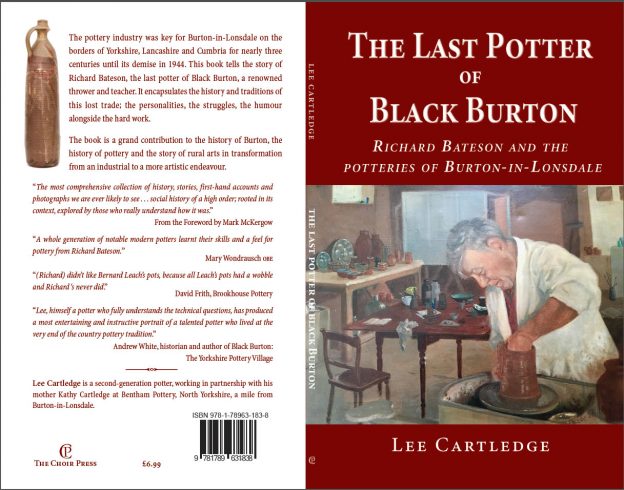

The Last Potter of Black Burton

The Last Potter of Black Burton is a book written by Lee Cartledge of Bentham Pottery and it is about the pottery industry of nearby Burton-in-Lonsdale that flourished for at least 300 years, before going into decline after the First World War. The last pottery closed in 1944.

There were at least 16 potteries in Burton that took advantage of the open cast coal and clay that was abundant around the River Greta. The book focuses on the Burton Potteries from the 1900s onwards and particularly on the very last potter, Richard Bateson.

In 1977, when Bentham Pottery had been in business for one year, Richard Bateson turned up at the pottery with some of his grandchildren (he would have been in his 80s at the time). He introduced himself to Kathy (Lee’s Mum) as the “last potter of Black Burton” and asked if he could throw some pots to show his grandchildren what he used to do for a living. Kathy was a bit nonplussed but gave him some clay. Within a few minutes it became apparent to Kathy that Richard was an astoundingly good thrower. He could create forms and shapes on the wheel with a dexterity and fluidity that she had never seen before and she had attended quite a few pottery events where prestigious studio potters of the day had been demonstrating. Richard could handle both small and large weights of clay with equal skill and she was impressed with the rapidity with which he achieved his forms. After this visit, Richard Bateson became a regular visitor to the pottery and he taught Kathy a whole range of new techniques that improved the way she made her pots. In turn Kathy has passed on these techniques to Lee who is now passing them on to his son, Jed, and also the numerous students that attend courses at Bentham Pottery. This visit began a relationship with the Bateson family, which continues to this day.

Richard Bateson began work at his father’s pottery, Waterside Pottery, in Burton at the age of 13 in 1907 and rapidly progressed to becoming one of the main throwers there.

The book follows Richard’s journey through the pottery industry. It examines the key characters, methods of production, working conditions and general antics of the potters. It looks into why the industry went into decline after the First World War and how the Burton potters failed to adapt to changing times and innovations within the industry relying instead upon their tried and tested techniques from the past i.e. hand throwing every pot on the wheel.

Richard ended up running the last of the Burton potteries, which was sadly forced to close its doors in 1944. He was really one of the very last men working in the country pottery tradition.

The story could well have ended there and 300 or so years of pottery traditions could have been lost if it wasn’t for a twist of fate caused by the Second World War that gave Richard a much needed life line. Rewind 4 years and the Royal College of Art (RCA) was evacuated to Ambleside due to German bombing raids on London. With no kilns or wheels in Ambleside, the RCA looked for nearby potteries that would fire students’ work and offer some work experience. They found Richard’s pottery in Burton and arrangements were made to facilitate this. RCA students became regular visitors to the pottery for the rest of the war. During the students’ work experience, Richard spent time teaching them how to throw pots on the wheel and he must have made a very favourable impression upon the RCA tutors, because after the war was over and the RCA had moved back to London, they contacted Richard and offered him a job teaching throwing. Richard accepted this invitation and so, in his early fifties, embarked on a new career as a pottery teacher at the RCA in London.

Studio pottery came of age after the Second World War. There was a large demand for hand thrown pottery caused in part by Bernard Leach’s “A Potter’s Book”. Richard went on to teach a substantial number of these emerging studio potters. These include potters like Allan Caiger-Smith, David Frith, and Gordon Baldwin. And so the traditions of the Burton pottery industry did not die, they were passed on to a new generation of potter. Richard had spent a lot of his life making hand thrown pottery look industrially made. He was now encouraged to teach how to make handmade pottery look handmade!

“The most comprehensive collection of history, stories, first-hand accounts and photographs we are ever likely to see… social history of a high order; rooted in its context, explored by those who really understand how it was.” From the foreword by Mark McKergow, Richard Bateson’s grandson

“A whole generation of notable modern potters learnt their skills and a feel for pottery from Richard Bateson” Mary Wondrausch OBE

“(Richard) didn’t like Bernard Leach’s pots, because all Leach’s pots had a wobble and Richard‘s never did.” David Frith, Brookhouse Pottery

“Lee, himself a potter who fully understands the technical questions, has produced a most entertaining and instructive portrait of a talented potter who lived at the very end of the country pottery tradition.” Andrew White, historian and author of Black Burton: The Yorkshire Pottery Village

The book owes a lot to the generous help provided by Richard Bateson’s grandson Mark McKergow in giving access to treasured family memorabilia and organising the publication.

The book is available for purchase at the pottery (where you can get a signed copy), or on Amazon

The author has also put together a 4.5 mile walking guide around the sites of the former potteries of Burton, which is available here: Pottery Walk

Here are a few reviews of the book:

Craven Herald

Lancaster Guardian