William Bateson 1826-1892 founder of Waterside Pottery Burton-in-Lonsdale

Prologue

Having written the story of Waterside Pottery in my book “The Last Potter of Black Burton”, I decided to look a little further into the past to the origins of the company and particularly the man that initially had the vision for it, William Bateson, the grandfather of the Last Potter of Black Burton.

William Bateson was an important figure in the history of the Burton-in-Lonsdale pottery industry, as he founded Waterside Pottery, which was the largest of the Burton potteries, the most modern Burton pottery and the most likely Burton pottery to succeed into the 20th century and beyond. Indeed, with the correct foresight, planning, decisions and investment in the early part of the 20th century there is no reason why Waterside Pottery could not still be in business today.

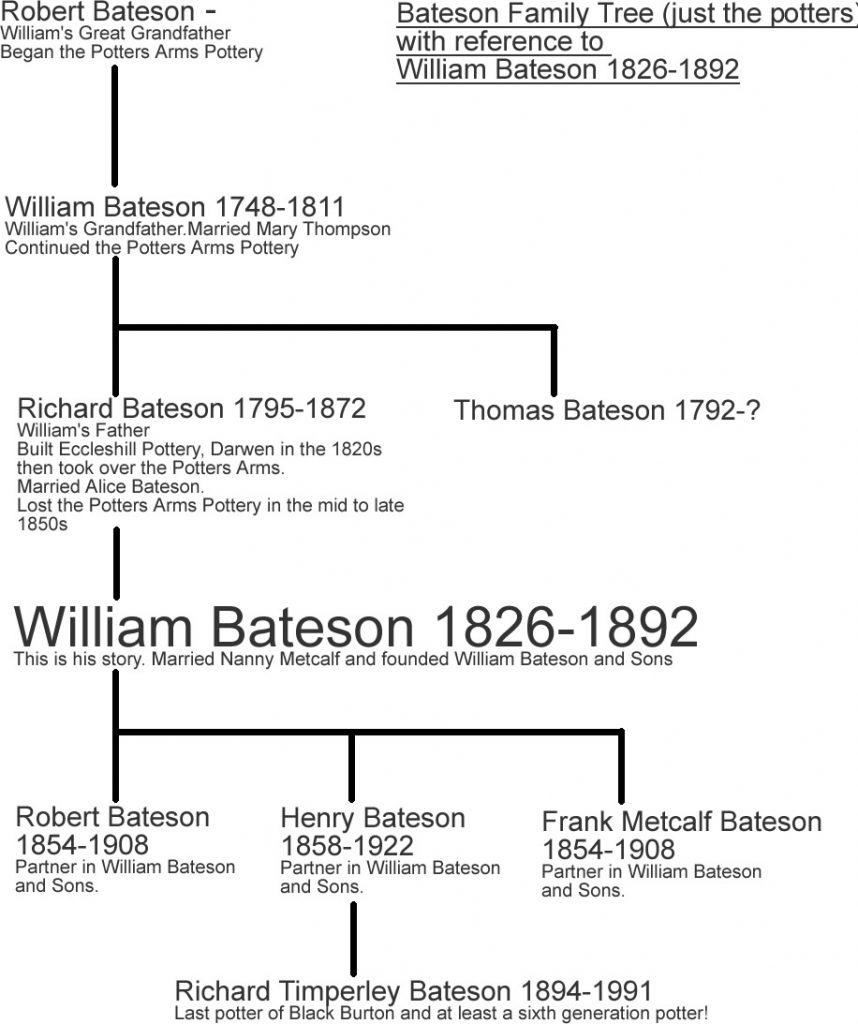

One of the problems of writing about the Burton potteries is that the Bateson family had a fondness for calling their sons William, Richard or Thomas, which can lead to much confusion. I think they solved this problem at the time by using nicknames. It’s just a pity that the nicknames weren’t recorded in parish registers and census information. With this in mind I thought it would be helpful to include the following family tree starting with William’s great grandfather, Robert Bateson (thankfully not a Richard, William or Thomas!):

I never intended this essay to resemble a small book. I thought a single A4 sized essay on William Bateson, would be a nice prequel for my book “The Last Potter of Black Burton”. However events and research changed all this! The original version of this essay was small, that is until I met Julie Gabriel-Clarke from the Burton in Lonsdale Heritage Group whilst visiting a large Burton jug (the “Craven Heifer Jug”) in Bentham and she offered to do some research for me on William Bateson. Julie’s research proved to be detailed and amazing and revealed new aspects of William’s life that I was previously unaware of. She provided me with the bones to hang the flesh of the essay on and I am very grateful to her for this. So I guess I blame Julie to some extent for the length of this essay, although she isn’t solely to blame, because I came across a blog about a row of houses (Dandyrow.co.uk) opposite where Eccleshill Pottery, where William once worked, was located and I sent an email asking if they knew anything about Eccleshill Pottery, not even really expecting a reply. Eileen Cowan from Dandy Row did get back to me and provided me with a wealth of information on Eccleshill, Eccleshill Pottery and the history of the Handle’s Arms Inn, for which again I am very grateful, but this also expanded the essay. But really I suppose I’m just trying to shirk responsibility here as I guess the real culprit responsible for the length of this essay is myself and my fascination with the history of the Burton Potteries!

The Potter’s Arms Pottery

William’s family owned and ran the Potters Arms Pottery in Duke Street, Burton-in-Lonsdale. The Potters Arms Pottery comprised of a public house with a pottery in the back yard. The pub was run in conjunction with the pottery.

William’s great grandfather, Robert Bateson began the business around 1740, the pottery/pub then passed onto William’s grandfather, also called William Bateson. William’s grandfather died at the age of 63 in 1811 leaving a widow, Mary and three daughters and two sons. The youngest son was William’s father, Richard Bateson.

William’s Father Richard Bateson

For a time Mary ran the business. She struggled with the unruly behaviour of her two sons, Richard (William’s father) and Thomas. This was possibly exacerbated by the death of their father when they were still teenagers. Mary ended up, possibly in desperation, sending her boys to a relation with a pottery in Blackburn/ Darwen to give her a break and possibly to give the boys some moral direction, as well as learn a trade. I have three sources for this information:

“William Bateson (William’s grandfather) died in 1811, aged 63, “master potter and householder”, leaving a widow and three daughters, and two sons (Thomas and Richard) aged 19 and 16. His widow continued to manage the pottery for a time. It is said that Thomas and Richard were unruly lads, wringing their mother’s hands to get money!” (Dalesman magazine March 1949, volume 10)

“William Bateson (William’s grandfather) was born in 1748, took over the property from his father and ran the business until 1811 when he died, leaving a wife and two sons, Thomas and Richard. His wife was unable to control the boys and packed them off to Darwen, to their uncle’s pottery” (unpublished essay on the Burton potteries by R.T Bateson and H. Bateson)

“His widow Mary and sons Thomas and Richard then ran the works, as well as owning a public house called “The Potters Arms”. The sons worked in Blackburn for a period in the early 1820s then returned to Burton and ran the pottery until c 1860” (Yorkshire Pots and Potteries, Heather Lawrence.)

I have not been able to definitely identify the relation/uncle with a pottery in Darwen/Blackburn. I suspect that the pottery was Grimshaw Park Pottery in Blackburn, as that seems to be the only pottery producing country wares at that time in that area. Grimshaw Park Pottery was set up by John Riley (sometimes spelt Ryley) in the early 19th century. I have not been able to determine if John Riley is related to the Batesons.

So it would appear that the young Richard (William’s father) and brother Thomas were sent to this relation/uncle for a period of rehabilitation. I have no doubt that this relation, presumably having made his own way in life, would have been ideal for handing out discipline and employment to two unruly lads and I’m sure he would have guided them back onto the straight and narrow path! Indeed, William’s father Richard seems to have thrived in this environment. I’m not sure how long Mary intended her boys to stay away from Burton, but Richard remained in Blackburn/Darwen into his early thirties. Around the 1820’s it seems Richard decided to branch out and open his own pottery. He rented a farm in Eccleshill (close to Darwen) and built a kiln on the site and ran a pottery and farm in tandem.

Eccleshill Pottery

“It must be noted that potteries opened elsewhere in Lancashire during this period, most notably in the Blackburn district. Here, an enclosure map of 1774 records the pottery at Broadfield, Oswaldtwistle, and by the early nineteenth century John Riley had opened Grimshaw Park Pottery in Blackburn. By the mid-1820s potteries were also working at Eccleshill, south-east of Blackburn, where Richard Bateson was the proprietor, and at Gaulkthorn, Oswaldtwistle, which was leased to John Riley. Both made black earthenware. Despite the decline of the Liverpool potteries, therefore, the Lancashire pottery industry still progressed, employing 500 people in 1841.” (Made in Lancashire: A History of Regional Industrialisation By Geoffrey Timmins, Steve Timmins)

“Eccleshill Pottery – Started c1824 by Richard Bateson of Grimshaw Park Pot House, Blackburn. The pottery produced tiles, chimney pots, firebricks and earthenware from clay extracted on site.” (A Guide to the Industrial Archaeology of Darwen, Including Hoddlesden, Yate & Pickup Bank, Eccleshill and Tockholes by Mike Rothwell)

Richard’s choice of Eccleshill as a location for a pottery would have been based on the following facts:

Clay was available on the site – In the 19th century this was a prerequisite for a pottery.

The site was rural – country potteries were predominately on the outskirts of towns, because of the smoke from firing the kilns.

Accessibility to coal – no problem here, as there was plenty of coalmines around Blackburn and Darwen within easy reach.

Access to a good market for selling wares – Richard would have known the market well after working at Grimshaw Park Pottery in Blackburn.

Affordability of the site – pottery was never a quick route to wealth, unless your name was Josiah Wedgewood!

According to the above article Richard would have made black earthenware (usually referred to as blackware), which was terracotta clay with a dense black lead glaze and was very popular at this time. I suspect Richard would have also made pots with a white slip decoration, in the Burton tradition.

Richard must have kept in contact with Burton-in-Lonsdale, as he went on to marry (and confuse Burton historians!) his cousin’s daughter Alice Bateson, from Burton. Alice was the daughter of John Bateson who ran Town End Pottery in Burton. Richard and Alice married on the 25th May 1825 at St John’s Church Preston. The wedding certificate states that Richard was resident in “Eccleshill in the parish of Blackburn” at the time of the marriage.

William Bateson was born in Eccleshill in 1826 and was their only son. They subsequently went on to have six daughters. William was baptised at Lower Chapel, Eccleshill in March 1826.

Shortly after the baptism of William the family moved back to Burton-in-Lonsdale and Richard took over The Potters Arms Inn. According to the land tax records, Richard Bateson was renting the Potters Arms Inn from his mother Mary Bateson in 1826. In 1831 Richard was renting the “house and pottery” from his mother. I’m not sure what prompted the move back to Burton, perhaps Richard and Alice wanted their children to be brought up in their home village, or maybe Richard’s mother Mary just offered a good deal in terms of rent to lure her new grandchild back to Burton?

William Bateson’s Early Life

By the time William was born the extended Bateson family were deeply intermeshed in the Burton potteries, with William’s uncles running Town End Pottery, Greta Pottery and Blaeberry Pottery.

William would have begun to learn the craft of pottery from his father at an early age. The pottery would have made traditional lead glazed terracotta country ware. The clay would most likely have been dug at Mill Hill in Burton. The pots would have possibly been decorated with white slip or even a black glaze (black-ware). This would have been in the days when the wheels were powered by a crank at the front of the wheel. I can imagine William spending a lot of his youth turning such a crank, so his father could make pots. I’m sure a lot of the children of potters learnt how to throw by endlessly watching their fathers throw whilst they provided the power for the wheel.

William probably had little choice in his career path. The sons of potters were expected to become potters themselves (and Richard Bateson only had the one son). Thankfully, as his life turned out, it seemed a good choice.

In the 19th century, it took a minimum of eight men (and one horse) to run a country pottery and stand any chance of making a living from it. It wasn’t like today, when one or two people can do the job. There was simply too much work to do for less than eight men when all the processes were done by hand and a lot of team work was required. The steam engine didn’t come to Burton until later in the century.

William would have been involved in the whole process, from digging the clay, processing the clay, powering the wheels, throwing the pots, glazing the pots, filling the kiln, shovelling the 10 tons of coal into the fire-mouths to fire the kiln, unloading the pots, packing the pots, selling the pots and looking after the horse and cart that were required for collecting the clay and coal as well as transporting the pots. And if that was not enough they still had a public house to run! It must have been a balancing act at times.

William would have been passed from pillar to post, from workman to workman to learn all aspects of the job and I’m sure that he would have also worked at his uncles’ potteries in Burton at times.

I suspect that they sold their pots to local markets, such as Kendal and Kirkby Lonsdale, as well as supplying some shops and dealing with customers direct from their pottery (as Bentham Pottery do today). It probably helped running a pub at the same time as running a pottery, as a potential pottery customer may have strayed into the pub first and plied with a bit of alcohol they may have found that their purse strings were somewhat looser than they intended. Also customers to the pub may have unsuspectedly ended up as pottery customers, leaving the premises with more than just a belly full of ale and a pickled egg supper! I wonder how many drunkards left the pub with a nice pot in a bid to appease an angry spouse the next morning. I also wonder how many pots were broken on the way home. I can’t help thinking that an early version of the “Great Pottery Throw-down” must have played out one night at the Potters Arms.

Richard undoubtedly paid his workers over the bar on a Friday night. This was common practise where pottery owners also owned pubs. The Baggaley family who ran the Baggaley Pottery as well as the Punch Bowl Inn in Burton certainly did this and I have heard this was the case with some of the potteries of Stoke-on-Trent. This must have been an excellent way of “recycling“ the wages.

The Potters Arms Inn and Pottery were actually owned by one Richard Wilkinson of Westhouse (near Ingleton). Richard’s mother, Mary, sublet the premises to him. Mary sadly passed away in 1833 at the age of 77. Richard Wilkinson died in 1835 and he was rather generous to Richard Bateson in his will:

“Also unto Richard Bateson the sum of £5 (equal £830 today) yearly for the term of his natural life. It is also my will and mind and I do hereby order and direct my trustees or the survivor of them of the Heirs, Executors or Administrators of such survivor do permit and suffer the aforesaid Richard Bateson to hold retain and keep the Mortgage Deeds belonging to the Potters Arms within Burton in Lonsdale aforesaid with all and singular the Pot Kiln, Workshops, Barn Stable and all other appurtenances thereto belonging and transfer the said Deeds unto him, he the said Richard Bateson yielding and paying unto them the amounts of the Mortgage with all and every expense with which I may have been connected with or concerning the said premises or any part thereof by Instalments yearly and every year the sum of thirty five pounds ( £5800 today) without any rent or interest whatever and that the said sum of thirty five pounds be divided along with the rents, and profits of my Real Estate as aforesaid.” (Richard Wilkinson’s will 17th January 1835, Richard Bateson is listed as one of the appointed trustees/executors)

So Richard inherited the deeds of the Potters Arms Inn and Pottery along with the outstanding mortgage as well as a yearly allowance for the rest of his life. I have tried to work out what the relationship was between Wilkinson and the Batesons, but have seemingly come up against a brick wall. I suspect that they were blood relations, but I haven’t been able to prove this. All I can say is that Richard Bateson seems to have done rather well out of the matter!

Over time, William became a fully proficient country potter and started to put roots down. William married Nanny Metcalf on the 18th May 1853 in Kirkby Lonsdale. Nanny was born in Ingleton from farming stock. Their first three children Robert, Richard and Henry were all born in Burton-in-Lonsdale (all three went on to become potters).

In the ordinary scheme of things I’m sure William would have inherited the Potters Arms Pottery from his father and continued to run it before eventually passing it onto his sons. However this didn’t happen due to an unfortunate event that changed everything. William’s father, Richard, had the misfortune to lose his entire property, both the pottery and the pub as the result of having stood surety for some money (The Dalesman magazine March 1949). Sadly the Dalesman article doesn’t go into any details about this.

A possibility as to how Richard lost the Potters Arms may be gleaned from events at Town End Pottery around this time. Town End Pottery was run by William’s uncle (on his mother’s side, not his Dad’s brother) Thomas Bateson. In1855 Thomas was declared bankrupt and indeed he was sent to debtor’s prison at Lancaster Castle for a time. This unfortunate incident played out over a few months and is recorded in the following newspaper articles:

The London Gazette, 3rd April 1855 states “Thomas Bateson, late of Burton-in-Lonsdale, Lancashire, out of business.-In the Gaol of Lancaster” is to attend a “Court for Relief of Insolvent Debtors. Saturday the 31st day of March 1855”

The London Gazette, 8th June 1855, states that “The following PRISONERS, whose Estates and Effects have been vested in the provisional Assignee by order of the court for Relief of Insolvent Debtors, are ordered to be brought up before the Judges of the said courts respectively, as herein set forth, to be dealt with according to law:”………”Thomas Bateson, formerly of the Town End Pottery, Burton-in-Lonsdale, near Hornby, Lancashire, Earthenware Manufacturer, and late a lodger in Burton-in-Lonsdale aforesaid, out of business”

Perry’s Bankrupt Gazette June 16, 1855, states that a hearing for “Bateson Thomas, of Burton-in-Lonsdale, earthenware manufacturer” is to be held 22nd June 1855.

The London Gazette, 6th July, states that Thomas Eastham, an Assigner (court official who is responsible for dealing with a bankrupt person’s assets and paying their debts as well as checking on their actions) has been appointed for Thomas Bateson.

The repercussions of this bankruptcy were still going on four years later when The London Gazette of 15 July 1859 reports on a court case looking into the debts of Thomas Bateson’s father who died 17 years previously, making me wonder if poor Thomas Bateson inherited the debts of his father?

Could Richard have stood surety for Thomas’s debts at Town End Pottery in the hope that Thomas would be able to raise capital and avoid going bankrupt? If this was the case then it’s hard not to see some honour in Richard’s decision, erroneous as it was. Unfortunately I have no proof of this, so Richard may well have put all his property up for a fool’s errand arranged late one drunken night in the Potter’s Arms Inn!

The Potter’s Arms Inn and Pottery were put up for auction in 1856.The following advert appeared in the Westmorland Gazette:

To Be Sold By Auction

At the House of Mr. Richard Bateson, the Potters’ Arms Inn, in Burton-in-Lonsdale, on Thursday, the 27th day of November instant, at six o’clock in the evening, either altogether or in the following Lots, and subject to such Conditions as shall be then produced,

Lot 1.-All that old-established and well-accustomed Inn or PUBLIC HOUSE, known by the sign of the POTTERS’ ARMS, situate in the Town of BURTON-IN-LONSDALE, in the West Riding of Yorkshire, together with the Brewhouse, Barn, Stables, Shippon, Yard, Garden, and Appurtenances thereunto belonging, and now in the possession of Mr. Richard Bateson.

Lot 2.-All that valuable POT KILN, with WORKSHOPS, WAREHOUSES, and other Appendages, together with the Ground adjoining the same containing about Twenty Perches, Customary Measure, situate behind the Potters’ Arms Inn, and now in the occupation of Messieurs Richard and William Bateson.

The Property is a Freehold Tenure, and in good repair; and in the Ground belonging to the Pottery are two excellent wells of pure water, to one of which a pump is attached. The Workshops are also spacious and commodious, measuring in length Thirty-two Yards and in breadth Eight Yards.

There is likewise attached to the Pottery a right of getting Clay upon the valuable Clay Allotments appropriated to the staple Manufacture of Burton upon the inclosure of the Commons and Wastes of the surrounding district.

In case they should not be Sold, the above Premises will, in the course of the same Evening, be Let either altogether or separately, and either from year to year or for a term, to be entered upon at May Day next.

Further information and particulars may be known by applying to the said Richard Bateson, or at the Office of Mr. Eastham, Solicitor, Kirkby Lonsdale.

Kirkby Lonsdale, 4th November, 1856. (Westmorland Gazette)

The following notice was placed in the Lancaster Gazette 27 June 1857:

NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN,

That the partnership heretofore subsisting between the undersigned RICHARD BATESON and WILLIAM BATESON, carrying on business as Stoneware Bottle Manufacturers, at Burton-in-Lonsdale, in the County of York, under the style or firm of “Richard Bateson and Sons,” was this day DISSOLVED, by mutual consent; and all Debts owing to and from the said Firm will be collected and paid by the said William Bateson, who will still carry on the business.

As witness our hands, this 17th day of June 1857,

W.BATESON,

RICH. BATESON.

Witness Jno. Thornber. (Lancaster Gazette 27 June 1857)

When I first came across this, I dismissed it thinking it related to Greeta Pottery in Burton, which indeed was a manufacturer of stoneware bottles. The Potters Arms Pottery by contrast was known for being a traditional earthenware country pottery. The owner of Greeta Pottery was another William Bateson (William’s Uncle) and he did have a son called Richard (William’s cousin) however closer scrutiny reveals that the company name in the above newspaper article is “Richard Bateson and Son”, had it been Greeta Pottery, then it would have had to be “William Bateson and Sons” so it can only really be our William and his father running this business. This highlights the absolute confusion of having a lot of Batesons in the same village with the same name following the same profession!

So it would appear that The Potters Arms was following market trends and had moved away from earthenware country pottery and had started making stoneware bottles around this time. This represents something of a Burton-in-Lonsdale historical scoop, as none of the history books mention this.

William and his father’s decision to move away from traditional terracotta country ware and produce stoneware bottles would have been based upon the fact that there was a large demand for stoneware bottles from the 1840s onwards and more importantly, they would have witnessed Greeta Pottery, Greta Bank Pottery and Blaeberry Pottery all in Burton and all successfully making a living producing stoneware bottles. It is just such a great pity that they had to sell up, as the business seemed to be moving in the right direction and I’m sure they would have done well making stoneware bottles in Burton at this time. I wonder where they were sourcing the stoneware clay?

The property was bought by James Fothergill. The pottery was converted into a joiner’s yard. The pub sadly changed its name to the Joiners Arms to reflect this new business.

I am not sure when the joiner’s yard closed, but the Joiners Arms was still going in the early 1980s and was one of the first pubs I ever drank a pint in (it was an easy walk from Bentham Pottery).

Eccleshill Pottery Revisited

With the loss of the Potters Arms Pottery, William was forced to find work elsewhere. Surprisingly it seems that the whole family including William’s father and mother upped sticks and moved to Darwen, Lancashire and William took over Eccleshill Pottery.

I’m not sure how the move to Darwen came about? I can understand that having lost both the pub and the pottery the family just wanted a completely new beginning. I guess the fact that William’s father had previously run Eccleshill Pottery must have been an influential factor in making this decision and that some contact with Eccleshill Pottery had been maintained.

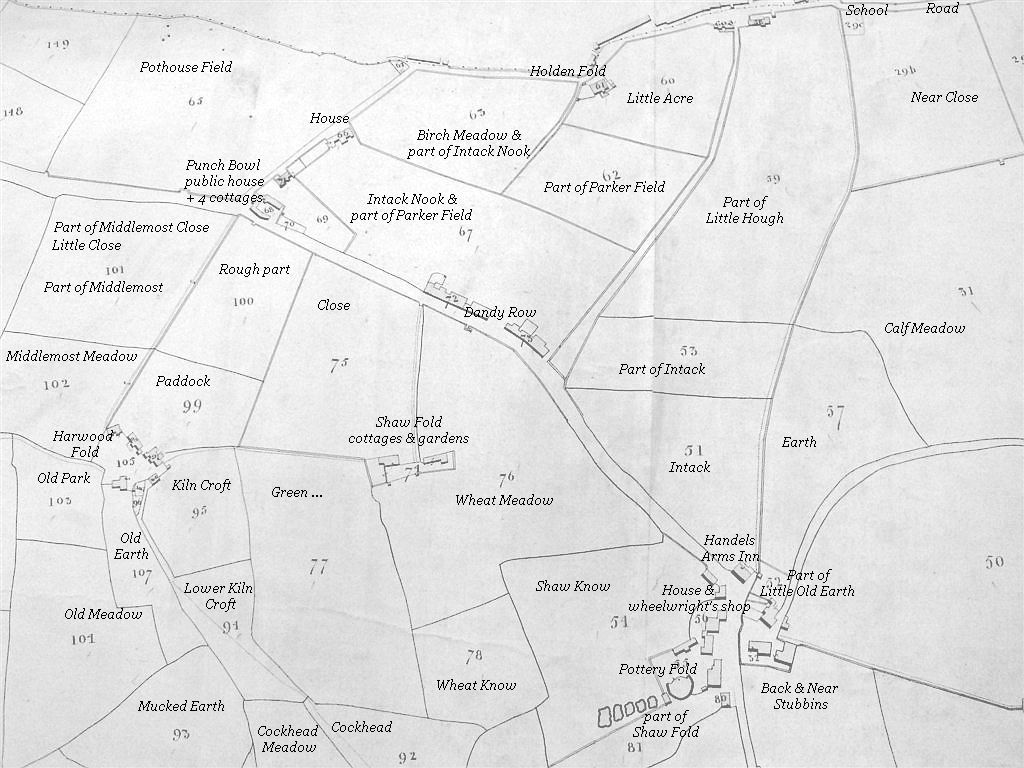

Eccleshill Pottery had passed on to at least two other owners after Richard Bateson. According to Mike Rothwell (A Guide to the Industrial Archaeology of Darwen), John Beswick and Ormerod Holden had run Eccleshill Pottery after Richard. Further enquiries via an Eccleshill blog (Dandyrow.co.uk) revealed that John Beswick had apparently also run the pub, the Handel’s Arms just over the road from the pottery, having married Peggy the landlady. When John Beswick died in 1843 at the age of 41, Ormerod Holden married John Beswick’s wife Peggy and continued to run the pub and pottery. The following advert appeared in the Preston Chronicle in 1853:

To BE LET, that old established and well accustomed PUBLIC HOUSE called the “Handel’s Arms Inn,” with 16 acres, 2 roods and 12 perches of excellent Meadow and Pasture Land, with suitable outbuildings, together with an Earthenware Pottery, comprising large kiln (lately erected,) working and drying sheds, colour-room, ware-room, and numerous other conveniences, with a good bed of potters’ clay adjoining, all in the occupation of Mr. Ormrod Holden, and situate at Eccleshill, distant three miles from Blackburn. On application, John Benson, of Eccleshill Colliery, will point out the boundaries of the premises and give further particulars. Tenders will be received until Saturday the 31st of December instant, by Mr. George Hunt, Land Agent, Preston.

4, Chapel-walks, Preston, 8th Dec, 1853 (Preston Chronicle, December 10th, 1853)

This must have seemed like the Potters Arms in exile to the Bateson family! I don’t think William rented the pub, but he did rent Eccleshill Pottery. This would have happened around 1857. The following advert from the Preston Guardian of 1858 announces Eccleshill Pottery had opened for business under new ownership:

ECCLESHILL

STONEWARE BOTTLE WORKS, OVER DARWEN.

WILLIAM BATESON begs to give notice, that he has commenced making spirit jars, porter bottles, ginger beer bottles, and all other kinds of stoneware on the above premises. He also feels grateful to those friends who have favoured him with their support, and hopes, by manufacturing a good article, to merit a continuance of their orders.

Tiles for malt and corn kilns made to order (Preston Chronicle 14 August 1858)

Eccleshill Pottery had originally been set up for the production of earthenware country pottery. William though wanted to produce stoneware bottles. This meant that he had to rebuild or even build another kiln as stoneware fires 200 degrees higher than terracotta and so needs a different kiln design to achieve this temperature. William was helped in this rebuild/building of the kiln by his cousin (another Richard!) whose father ran Greeta Pottery in Burton-in Lonsdale (Dalesman magazine). It is possible that this cousin stayed on at Eccleshill Pottery and worked for William.

William’s parents, Richard and Alice moved to the centre of Darwen. Alice sadly died in 1858 at the age of 62 and you can’t help thinking that her demise may in part be due to the stress of losing everything and having to move away from Burton.

The 1861 census finds William, as a 35 year old, as the head of the household at Eccleshill Pottery. He is listed as a potter and farmer employing seven men and one boy. The same census finds Richard (William’s father) living with his daughter at Cotton Hall Darwen. He is listed as a potter and I suspect he must have been working for William at Eccleshill Pottery.

“Eccleshill Pottery….The last records of the works appears in the mid 1860’s when William Bateson was making stone bottles at the site.” (A Guide to the Industrial Archaeology of Darwen, Including Hoddlesden, Yate & Pickup Bank, Eccleshill and Tockholes by Mike Rothwell)

The search for the location of Eccleshill Pottery

A Google Street View of Eccleshill proves to be very interesting. Eccleshill is a very small collection of houses and farms. In the middle of Eccleshill there is a gated driveway with “Pottery Farm” painted on the gate. More interestingly still, there is a large round stone with a hole in the middle, with “Pottery Farm” carved into it. Could this stone have been excavated from an old pottery blunger and upcycled? Mike Rothwell (A Guide to the Industrial Archaeology of Darwen) states that Eccleshill Pottery was “situated to the rear of the Handel’s Arms public house”. The Handel’s Arms closed in 2002. I was able to find an old photo of it on Google and this photo matches exactly (minus the public house signs) with the building to the right of Pottery Farm, proving that Pottery Farm is indeed the former location of Eccleshill Pottery.

Today, Pottery Farm is a prize winning alpaca farm that trades as Pottery Alpacas. I’d like to think that William Bateson was responsible for introducing alpaca farming to the country, but I think this is unlikely. The “pottery-cum–farm” as described in the Dalesman article was likely to have been a small holding with a few animals mainly providing food for the family.

I have contacted the present owner of Pottery Farm via Facebook and they do occasionally get people approaching them wanting to look for bottles and pots on the land. They also confirmed that the large round stone outside his driveway was found on the land whilst renovating the house, so it is very likely pottery related? I suspect a blunger stone, a glaze grinder or possibly even a fly wheel?

Shaws of Dawen, Waterside

Adjacent to Eccleshill (Darwen) is another small hamlet called Waterside which is an interesting name to any Burton Pottery historian. Could William have named Waterside Pottery, Burton after this Waterside? Waterside near Darwen is famous for having a very successful pottery factory, still in business today. Shaws of Darwen have made ceramic sinks for the last 125 years at their factory in Waterside. They didn’t invent the Belfast sink, but their factory has been making Belfast sinks for longer than any other pottery. Shaws of Darwen began in business when the son of a local coalmine owner discovered that a by-product of his father’s coal mine was a rather fine fireclay. He decided to utilise this material and base a business around it. Shaws of Darwen began in 1897 and expanded in 1908 with the building of their factory at Waterside. This all happened 30 or so years after Eccleshill Pottery though. However it does prove the suitability of Eccleshill for pottery manufacture and the availability of stoneware clay in the area. Also I feel that the close proximity of Shaws of Darwen to Eccleshill Pottery could have had important ramifications if business at Eccleshill Pottery had continued into the 20th Century. I will revisit this point later.

The return to Burton-in-Lonsdale

William and Nanny had seven children. The first three were born in Burton whilst William was still working with his father at the Potters Arms Pottery; the remaining children were born in Eccleshill. Nanny sadly died in 1866 at the age of 37 and I can only imagine that she died in childbirth, with the child surviving the birth, as their last daughter was born in the same year (1866) and very tellingly was named Nanny after her mother. This event must have been devastating for the entire family and it seems that this tragedy was the catalyst for William’s return to Burton-in-Lonsdale.

William would have been 40 years old when Nanny died. He was left with a young family of seven children, the oldest being 12 years old. I can only guess that his decision to return to Burton-in-Lonsdale was based upon a need to return to his wider family and familiar small village to help him bring up his children. I can’t imagine how hard it was giving up everything they had built up at Eccleshill Pottery. Without this sad event though, there would have been no Waterside Pottery in Burton-in-Lonsdale.

Nanny was buried at, St James Church, Over Darwen 17th June 1866.

William, now aged 42, moved back to Burton-in-Lonsdale sometime around 1868 (unpublished essay on the Burton potteries by R.T Bateson and H.Bateson).

William’s father Richard also moved back from Darwen. The 1871 census records Richard living in Lancaster with his daughter. He is listed as an “unemployed potter”. Richard very sadly died in 1872 at the age of 77. He was buried in Burton-in-Lonsdale.

Eccleshill Pottery under William Bateson would have lasted for approximately 10 years, from 1858 to about 1868.

Greta Bank Pottery and Blaeberry Pottery

Once back in Burton, William found work at Greta Bank Pottery, which was owned by James Parker who at the time was mainly producing stoneware bottles. William worked as the foreman at Greta Bank Pottery and did a lot of “travelling” for James. I think “travelling” implies that he went on the road to source potential customers and acquire orders. This would have proved very useful networking for future business.

William rented Blaeberry Pottery from his uncle, John Bateson. Blaeberry Pottery hadn’t been used for a number of years and was semi derelict. The kiln, known affectionately as “old Timothy” was in a state of disrepair and needed major renovations. Outside of work hours, William and his sons, started to repair the kiln and get the pottery ready for production. William and family were all resident at Blaeberry Pottery by the time the 1871 census was recorded.

“He saved all the money he could, and rented for £20 a year, Blaeberry Pottery, which had belonged to John and Elizabeth Bateson (John was William’s uncle), which was now in ruins. He lived in the dwelling-house which was then attached to the pottery. During the evenings, William, with his boys, re-built the pottery, which he eventually bought, re-naming it Waterside” (Dalesman magazine March 1949, volume 10)

Blaeberry Pottery was something of a “potters paradise”, as it had opencast coal and open cast stoneware clay in the field adjacent to the pottery, so fuel and materials were effectively free. Added to this, there was a steady supply of water, courtesy of the River Greta, which ran directly past the pottery.

I’m not sure how long William worked at Greta Bank Pottery, or when the first kiln was fired at Blaeberry Pottery. It’s possible that in the early days, William worked at Greta Bank Pottery at the same time as running Blaeberry Pottery? The 1871 census states that William is at “Blaeberry Pottery in Low Bentham Ward employing 4 men 2 boys and 3 bottle casers”, which would imply that Blaeberry Pottery was in production at this time.

William’s sons, Robert, Richard (yet another Richard!) and Henry all worked for their dad. William’s third son Henry, or Harry as he was always known was a natural on the pottery wheel. Harry went on to become a phenomenal thrower. In his prime, Harry was able to throw 120 six-gallon bottles in a day. The weight of a ball of clay required to make a six-gallon bottle is 66lbs! I mention this in my book “The Last Potter of Black Burton”, but I feel it is worthy of another mention here.

The company William Bateson and Sons was formed sometime in the early 1870s. William also changed the name of Blaeberry Pottery to Waterside Pottery around this time.

The 1881 census states that William is resident at Waterside Pottery employing 9 men and his eldest three sons are described as “Father’s assistants”.

Around the mid-1880s, James Parker decided to sell Greta Bank Pottery. I’m not sure what James’s reason was for this. It’s possible that James just wanted to retire and had no natural heir to the pottery? It’s also feasible that James realised the “Tour de Force” that was William Bateson and Sons and decided to quit whilst he was still ahead?

I feel sure that the sale of Greta Bank came as a surprise to William. I think William realised that the sale was too good an opportunity to miss, as it would effectively eliminate competition at the same time as acquiring all of Greta Bank Pottery’s customers.

William Bateson and Sons bought Greta Bank Pottery from James Parker in 1887.

“James Parker worked the pottery (Greta Bank Pottery) until 1887, when it was bought by William Bateson who had worked and travelled for James since his return from Darwen about 1870” (unpublished essay on the Burton potteries by R.T. Bateson and H. Bateson)

William Bateson and Sons finally bought Waterside Pottery in 1888 after renting it for many years.

It is testament to the strength of the stoneware bottle industry at this time that William Bateson and Sons were able to persuade the banks to allow them mortgages on two potteries within a year of each other.

For at least a decade William Bateson and sons ran Waterside Pottery and Greta Bank Pottery in tandem.

Waterside Pottery

The 1891 census records William at the age of 65 living at Chapel Lane, Burton-in-Lonsdale, with his occupation being “Living on own means”. This would suggest that he had retired from pottery at this time and left his sons to run the business.

Sadly, William died at the age of 66 on 20th April 1892, leaving behind him a pottery legacy and a seemingly secure future for his family. William was buried at All Saints Church in Burton-in-Lonsdale. William left £1958 14s. 7d in his will which is approximately £298k in today’s money and must have been a considerable fortune for a potter from Burton.

“This is the last will and testament of me William Bateson of Burton in Lonsdale in the county of York, pot manufacturer. I revoke all other wills heretofore made by me and appoint my sons Robert, Henry and Frank Metcalf trustees and executors of this my will. I give and bequeath to my grandson William Bateson my gold watch and chain for his own use. I direct that my daughter Nanny shall have the use of my household furniture and effects for the term of her life provided she shall so long remain unmarried and from and after her decease or marriage I direct that the same shall fall into and form part of my residuary estate hereinafter mentioned. I give and bequeath the following pecuniary legacies, that is to say: to my son Richard four hundred pounds, to my daughter Hannah More nine hundred pounds, to my said daughter Nanny ten hundred pounds subject to the payment of my debts, funeral and testamentary expenses and all the pecuniary legacies heretofore bequeathed. I give devise and bequeath all the rest residue and remainder of my estate real and personal whatsoever and wheresoever unto and to the use of my said sons, Robert, Henry and Frank Metcalf in equal shares as tenants in common provided always and upon the express condition that the said sons allow my said daughter Nanny during her life or until her marriage should she desire to do so to occupy the dwelling house and premises which I now occupy free of rent in witness whereof I have this my last will and testament set my hand this twenty ninth day of December one thousand eight hundred and ninety one. William Bateson” (will and last testament of William Bateson 29/12/1891)

William’s sons Robert, Henry and Frank carried on the business at Waterside Pottery, introducing a steam engine and then expanding the pottery around 1900-1905 from one to three kilns to cope with the demand for stoneware bottles. Waterside Pottery went on to become the largest and arguably the most successful Burton pottery, particularly from the 1890s up to the First World War. The story of Waterside Pottery is available in my book, “The Last Potter of Black Burton”.

Epilogue

William Bateson recovered from two traumatic incidents in his life that he had little control over; Firstly, the loss of the Potters Arms Pottery and then later losing his wife and having to give up Eccleshill Pottery. The fact that he was able to successfully begin again after both of these events shows the remarkable mettle of the man and I am left wondering what he could have achieved without these two setbacks?

But for the death of a mother, Eccleshill Pottery would have continued. William Bateson and Sons would surely still have been formed but Waterside Pottery in Burton-in-Lonsdale would never have existed. How would Eccleshill Pottery have fared in this alternative future? I suspect if they continued making stoneware bottles, they would have prospered up until the First World War and then they would have started to slowly decline, as happened at Waterside Pottery. The question is would being in a different location have influenced the choices they made to prevent this decline in trade happening and secure the future of the pottery. Ironically a possible solution was literally three fields away behind Eccleshill Pottery. Shaws of Darwen were using the exact technology that Eccleshill Pottery would have needed to invest in to stay in business as an industrial pottery beyond the 1920s. Shaws were working with plaster moulds and slip casting. They would have employed mould makers, pottery engineers, kiln builders and designers and, I suspect, would have had strong links with the potteries of Stoke–on-Trent. At their peak in the 1920s Shaws were employing 600 people on a 26 acre site. Surely Eccleshill Pottery would have been influenced, by what was literally going on in their backyard and picked up on the advantages of plaster moulds and possibly poaching some of Shaws’ employees? It is also not beyond the realms of possibility that Eccleshill Pottery and Shaws of Darwen could have collaborated, after all their wares were not in direct competition. Perhaps in an alternative future, Shaws and Batesons of Darwen, Waterside, would exist, producing bespoke sinks and tableware.

When writing about events that happened so far in the past it is inevitable that mistakes and miss-interpretations can be made. For me the only Achilles heel of this essay is that I have been unable to find any details of the relation/uncle that had a pottery in Blackburn/Darwen. I have credited William’s father with building Eccleshill Pottery, however there is a possibility that the relation/ uncle may have built it, if his name was also Richard Bateson (not an uncommon name within the Bateson family!). Suffice to say that William’s father was sent to live and work at a relation’s pottery in or near Darwen as a young man and ended up working at Eccleshill Pottery, which he may have built. Further research may reveal more…..

I would have struggled to write this without the research provided by Julie Gabriel-Clarke of Burton-in-Lonsdale and Eileen Cowan of Eccleshill and I would like to thank them here for all their efforts. I also found the following two articles invaluable; the Dalesman article of 1949 and the unpublished essay on the Burton potteries by R.T. Bateson and H. Bateson. The Dalesman based their article around the reminiscences of William’s youngest daughter, Nanny who would have been 82 years old at the time the article was published.

I am grateful to Jeremy Bradshaw and Sue Ellis (both descendants of William Bateson) for the following:

William Bateson (1826-1892) had 7 children with his wife Nanny Metcalfe (1829-1866).

Robert Bateson (1855-1908) – Born in Burton. Married Susan Jane Kidd and had 6 children. Robert split from William Bateson and Sons in 1902, because he didn’t think the company was moving in the right direction. He sold his share: and bought and ran Greeta Pottery until his untimely death in 1908.

Richard Bateson (1856-1934) – Born in Burton. Married Catherine Rooney and had two children in 1896 and 1898 in the USA. Richard’s occupation on the 1881 census is described as”Father’s assistant (Stone bottle)”. He obviously then chose to move away from pottery.

Henry Bateson (1858-1922) – Born in Burton. Married Alice Timperley. Father of Richard Timperley Bateson (The Last Potter of Black Burton). Henry was the main thrower and joint owner of Waterside Pottery.

Martha Alice Bateson – (1861-1890) – Born Eccleshill, Lancashire

Hannah More Bateson – (1862-1945) – Born Eccleshill, Yorkshire (it is possible that Yorkshire is a mistake on the 1881 census)

Frank Bateson – (1864-1938) – born Eccleshill, Lancashire. Married Mary Ann Triffit. Joint owner of Waterside Pottery with his brother Henry

Nanny Bateson – (1866-1959) Born Eccleshill, Lancashire.

Lee Cartledge (Bentham Pottery) – 2023