Bradshaw’s Pottery (old Bridge End Pottery) 1770- 1886

My recently published book, The Last Potter of Black Burton, focussed on the pottery industry of Burton-in-Lonsdale from 1900 to its demise in 1944. Regrettably I left out the story of Bradshaw’s Pottery. The reasons for Bradshaw’s Pottery exclusion is that it closed in 1885 and it was really lost beyond the memory of the potters and people that I had interviewed and met over the last 40 or so years. The following article is an attempt to rectify this; and to try and build a larger picture of the history of pottery in Burton.

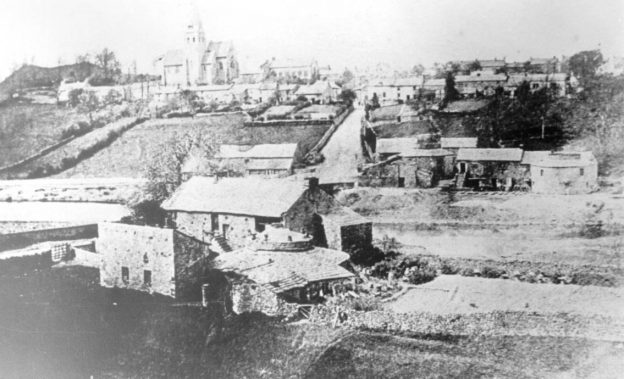

Bradshaw’s Pottery or Bridge End Pottery is the pottery with the prominent large round kiln in the foreground of the classic photograph of Burton-in-Lonsdale taken in 1870 (before the old Chapel of Ease, to right of the new church, was demolished).

Joseph Bradshaw built Bridge End Pottery or Bradshaw’s Pottery as it was better known in 1770 after working as a thrower at one of the other Burton potteries for a decade prior to this. Joseph was originally from Staffordshire where he learnt his craft. I have found the following references to Joseph Bradshaw and his Staffordshire connection;

“The Bridge End pottery, which is in the township of Bentham, was built about one hundred years ago by a Staffordshire man of the name of Bradshaw. The establishment is still carried on by his descendants Messrs J. and B. Bradshaw. The manufactured goods of all these potteries meet with a steady sale and they are sent through a wide district. The sale of the black ware is confined to the neighbourhood and a few places in Lancashire, Westmorland and Cumberland.” (Lancaster Guardian, 1875)

“Judging by family traditions, there seems to have been some distant connection with the great pottery industry which grew up in Staffordshire in the eighteenth century. It is said that Joseph Bradshaw, about 1760 came from Staffordshire” (Dalesman magazine, March 1949)

“Many inhabitants of the present day can have no idea of the smallness of wages at Burton-in-Lonsdale over 100 years ago. At that time a young man of the name Joseph Bradshaw came from Staffordshire to work at one of the Burton potteries, and as he was a skilful workman at his craft he secured the highest wages given at the establishment. Many a workman of the present day can earn more in nine and a half hours than he earned in seventy two hours. His standing wage was nine shillings a week. It is true provisions were much cheaper and his board and lodgings only amounted to two shillings and six pence per week. In consequence of a rise in provisions he had to pay an additional sixpence” (Lancaster Guardian, 1875)

Joseph was born in Staffordshire in 1736. It is possible that he was born at Norton le Moors (very close to Burslem, the heart of the Stoke pottery industry). The following extract from a family history suggests this could be the case using some rather clever detective work:

Joseph and Esther Bradshaw had eight children baptised in Thornton in Lonsdale between 1763 and 1780, the oldest being Sarah who married Robert Parker. Among the children were two sons by the name of Thomas, the first and last sons, but neither of them survived infancy. This may be an indication that Joseph Bradshaw’s father was Thomas Bradshaw, and a baptism has been found for a Joseph Bradshaw, son of Thomas and Sarah Bradshaw of Stoke parish who was baptised at Norton le Moors on 19th March 1737. However, further research would be needed to determine whether this was the correct baptism for Joseph Bradshaw, potter of Black Burton. (“The History of the Parker, Firth and Associated Families”, published by Julia Henderson, Acorn Family History Services, 2020)

According to the Dalesman magazine of 1949, Joseph moved to Burton around 1760, which would make him 24 years old at the time. The year prior to this event another Staffordshire potter of a similar age to Joseph founded a new pottery in Burslem, Staffordshire. His name was Josiah Wedgwood.

In 1762 Joseph married Esther Rumney, presumably a girl local to Burton;

“Joseph Bradshaw married Esther Rumney at St. Mary’s in Lancaster on 12th April 1762, the documentation for the grant of the marriage licence showing that he was “Joseph Bradshaw of Black Burton in the county of York, potter”…. (“The History of the Parker, Firth and Associated Families”, published by Julia Henderson, Acorn Family History Services, 2020)

The question that really interests me is why would a young production thrower move one hundred or so miles from the ceramic heartland of Stoke-on-Trent to work in a pottery at Burton-in Lonsdale? Henry Bateson (son of the last potter of Burton) cites a reason for this this in the following extract:

“During the mid-1700s work practises in the Staffordshire potteries changed, using a casting method of pottery rather than a throwing method, leading to many throwers seeking work elsewhere. One such thrower was a Joseph Bradshaw. Joseph Bradshaw bought the site on Bentham Moor in 1770, and built a pottery.” (Henry Bateson writing in Glimpse of Burton’s Past, 2000)

The “casting method” of producing pots that Henry refers to is slip casting, where a liquid clay (slip) is poured into a plaster mould and left for 20 minutes or so (depending on the wall thickness required of the pot) to build up a layer/skim of clay (the cast) on the inside of the mould. The slip is then emptied out and the mould and cast are left to dry before being separated. According to Simeon Shaw (the history of Staffordshire potteries, 1829) plaster moulds were first shown to the Staffordshire potteries in 1743 and soon after the plaster mould techniques were learnt, adapted and put to use within the Staffordshire pottery industry. So it would seem that Henry Bateson’s argument has to be considered as it certainly fits the time-line. However slip cast pottery on an industrial scale wasn’t viable in the 18th century, because the potters had not worked out how to reduce the water content of the slip and suspend the clay particles in the water, a process known as deflocculation. Without adding deflocculant to the slip the clay would take a long time to absorb into the plaster mould due to the slip’s high water content, this high water content would also cause a high shrinkage rate of the resulting pots leading to cracking and excessive warping and the slip would separate into layers of clay and water in the mould causing uneven casts. Moulds had to be agitated to prevent this settling out and sometimes multiple casts of moulds had to be done to attain the right wall thickness. Effective methods of deflocculation (usually by adding sodium silicate to the slip) were only developed in the late 19th century (Mold Making for Ceramics, Donald E.Frith, 1985). Because of this problem, very little slip casting occurred during the 18th century. Instead of slip casting, press moulding became the standard method for use with plaster moulds during the 18th century. Press moulding involved rolling out slabs of clay and literally pressing them into the plaster moulds to create the cast. A new genre of potter was born, the presserman. Press moulding is a lot slower than throwing, so the presserman would only make pots that could not be formed on the wheel.

The only real threat to throwers in the 18th century came with the development of the jigger and jolly wheel. According to Donald E. Frith (Mold Making for Ceramics, 1985), “the jigger and jolly system was well established by the middle of the 18th century”. The jigger and jolly was a semi mechanical method of press moulding a pot. The presserman would press or roll out a weighed piece of clay to form a round disc, known as a bat. The bat would then be placed inside or on top of a plaster mould in a metal chuck that would rotate on a wheel. A template would then be lowered onto the mould and thus create the pot. These early jigger and jolly wheels though were not the sophisticated steam driven machines developed in the mid-19th century at the Wedgwood Etruria works. They would have been powered by a boy rotating a crank wheel. The templates were sometimes hand held or the potter’s hands forming the exposed surface with no template. Things improved when the template was fixed onto a lever. The missing link though for efficient production in the 18th century was the development of the “batter out” machine, also known as the “steam-spreader”. The batter out machine mechanically made the bat to be fed into the jigger and jolly thus making the presserman redundant and the whole process a lot faster. There was much worker resistance to the introduction of these machines when they were introduced in the 1860s (www.thepotteries.org)

The jigger and jolly machines took over the production of plates, cups and bowls from around the mid-18th Century (Donald E. Frith). However larger pots, enclosed forms and any pot that featured an undercut (so couldn’t easily be released from a mould) were the sole preserve of the thrower at this time, so the jigger and jolly machines didn’t represent a significant threat to a good production thrower. A fully trained production thrower could usually compete with a jigger and jolly machine producing the same product anyway, especially with these early machines. Richard Bateson (the last potter of Burton-in-Lonsdale) proved this in the mid-1940s when he was able to make one gallon bottles faster on a pottery wheel than a man operating a jigger and jolly machine making one gallon bottles.

The disadvantage of the jigger and jolly machines was a lot of moulds had to be made and stored for each shape. (Lots of moulds of the same shape were required as the pots had to be left in the mould to dry sufficiently before they could be released) whereas a thrower could repeat produce any shape with just his hands. The disadvantage of a production thrower was the amount of time it took to train them up, which would be anything from 5 to 10 years, whereas a relatively unskilled person could operate a jigger and jolly machine.

There is no doubt that the introduction of plaster moulds together with scientific and engineering advances eventually all but replaced the need for hand throwing on the potter’s wheel, but this happened very gradually over 200 or so years. The thrower still reigned supreme in the 18th century, as the technology and science were not yet ready to replace him. It wasn’t until the mid to late 19th century that the throwers were really beginning to feel the pinch. The following case of arbitration from 1891 is quoted in Harold Owen’s ‘The Staffordshire Potter’, written in 1901:

“The thrower’s case is an interesting one, and illustrates the great changes that have taken place in potting during the period covered by the great arbitrations in this trade. The thrower’s wheel – the first machine perhaps, in any industry – no longer occupies the prominent producing position it once did, for most of the articles that were made by the thrower are now taken away from the wheel, and are either pressed or made on the jigger. Seventy-five per cent of these have been taken away from him, and the articles left to him have been increased in size” (Workmen’s case, arbitration of 1891)

“Taking the thrower as an example, that which was formerly entirely done by the men is now done on the machine by women and boys equally well for the purposes of the manufacturer, and the result is that machinery drives out these men from positions which they previously held alone. If there were any added wage given to the thrower at the present time the result would be his extinction the more rapidly.” (Manufacturer’s case, arbitration of 1891.)

Interestingly Wedgwood does actually employ one thrower to this day. I met him when we visited Wedgwood in 2018.

The Staffordshire which Joseph Bradshaw left in the 1760s was definitely a boom town. John Ward talks about this with reference to pottery manufacture and the six towns that formed Stoke-upon-Trent in his book, ‘the Borough of Stoke-upon-Trent’ written in 1863:

“The rapid advance of the manufacturers, and the consequent increase of the population, reckoning from about the middle of the 18th Century, have, perhaps, not been surpassed relatively, during the same period, in any of the great trading and manufacturing towns and districts of England”

Between 1738 and 1785, the population of Stoke had risen from 4000 to 15000. By 1838 the population was 63000 (John Ward). The demand for pottery was increasing exponentially, which in turn meant more jobs and an influx of workers to fill them. The success of the potteries had a knock on effect for the region and economy as a whole. The industrial revolution was on the very cusp of happening. Steam engines were about to move into the factories. Canals were being built and planned around the country. Josiah Wedgwood, having been one of the main advocates and promotors of a canal connection to Staffordshire (particularly one that would pass his factory), cut the first sod of the Trent and Mersey Canal in Burslem in 1766.

Joseph Bradshaw was definitely moving against the tide leaving Staffordshire in 1760.

So given that it is very doubtful Joseph was forced out of work due to unemployment or even impending unemployment, we can only assume that he went to Burton voluntarily. Was Joseph actively sought after and poached by a Burton pottery in order to learn from him the presumably more advance techniques of the Staffordshire potters? Was he chased out of town by some estranged husband? Was the local constabulary after him for some misdemeanour? How did he even know that a pottery industry existed in Black Burton? Perhaps Esther Rumney was holidaying in the Staffordshire area in the 1750s, where she met and fell in love with Joseph Bradshaw? Okay, that one is very unlikely. Did people actually go on holidays in the 18th century and if they did, would they choose Staffordshire? I have found though throughout my life that unlikely events are sometimes just as likely to occur as likely events!

The best theory I can come up with for Joseph’s relocation is that one of the Burton potteries perhaps lost one of their main throwers and needed a replacement quickly. Presumably they couldn’t find a replacement in or around Burton, nor did they have the time or patience to wait the 5-10 years to train up a new production thrower. The Burton pottery in question possibly had a contact with a Staffordshire pottery or even a company in Staffordshire that supplied some of the sort after fine clays that were being imported to Staffordshire from Devon and Cornwall. The Burton Pottery thus dually dispatched a letter asking if they knew any thrower that would be interested in moving up to Burton. Somehow Joseph was approached regarding this. Joseph was perhaps a restless young man desperate to do the 18th century equivalent of a gap year and decided to take the bull by the horns and give it a go. After all he could always go back to Stoke if things didn’t work out. Well that is my best guess. If you can think of anything more plausible then please contact me. If you have in possession the diary of Joseph Bradshaw, potter of Black Burton then even better!

What the young Joseph Bradshaw thought on arriving in Burton-in-Lonsdale is anybody’s guess. Did he arrive by stage coach? Had he walked and hitched lifts on horses and carts? Did he just arrive with the shirt on his back? I am not sure which Burton pottery he worked at prior to building his pottery, it can’t have been Waterside Pottery, Greta Pottery or Greta Bank Pottery as these had yet to be built. I think it would have been one of the old established larger potteries, so probably Town End Pottery, or the Baggerley Pottery. I’m sure his Staffordshire accent would have been a great novelty to any Burtonians he encountered.

Joseph would have been employed making terracotta country ware pottery, perhaps with some slip decoration. This was the days before the demand for stoneware bottles. Despite the Lancaster Guardian article of 1875 claiming that wages around this time were very meagre, Joseph was able to save enough money to purchase land and build his own pottery after ten years of working in Burton. I can only imagine how delighted the owner of the Burton pottery was when Joseph announced he was going to leave and set up on his own in direct competition in the same village!

“1770 – Joseph Bradshaw paid £20 to Rowland Tatham for a parcel of ground situate lying and being on the south side of Burton Bridge (being part of the allotment which was set out for the said Rowland Tatham on Bentham Moor).” (From the deeds of Bridge End Cottage)

Interestingly the land Joseph bought was on the south side of the River Greta, which is actually in the township and parish of Bentham and not Burton, so in a way Joseph built the first Bentham Pottery.

Joseph named the pottery Bridge End Pottery and went into production around 1770. The previous year Josiah Wedgwood had opened his third pottery, the iconic Etruria Works.

Joseph would have continued producing country pottery wares as demanded by the locality, using the Burton black ware/terracotta clay dug open cast around Mill Hill (near Greeta House). A few shards of pottery have been dug up in the garden where the kiln of Bridge End Pottery once stood and they reveal terracotta clay with some white slip trailing and a lead glaze.

I would love to be able to point people in the direction of pottery wares directly attributable to Bridge End Pottery, but this is not possible as, typical to Burton, the pots were not stamped with the manufacturer’s name and as a result any piece of terracotta thought to be Burton could possibly have been made by the hands of Joseph Bradshaw.

Manufacturing pottery at this time would have been hard work. Steam engines didn’t arrive in Burton until the late 19th century. Digging and processing the clay would have been all done by hand. The potter’s wheel would have been turned via a crank by an assistant. Eight tons of coal would have to be shovelled into the kiln to fire it to the correct temperature for the lead glaze to melt. Candles and oil lamps would have provided the light source inside the pottery. Joseph would probably own a horse and cart for transporting pots to market. I would guess that six to eight people would have been employed in total. There is a great account written in the Lancaster Guardian of 1875, describing the pottery process at the Baggerley Pottery, which although written 100 years after Joseph Bradshaw built Bridge End Pottery, is probably very comparable.

I’m sure Joseph would have introduced the Burton potters to some new and different pottery techniques as a result of learning his craft in Staffordshire. Could he have possibly brought the tradition of making puzzle jugs to Burton? Did any other potters come to Burton from Staffordshire? The Burton potters of the early 20th century were certainly using Staffordshire pottery vocabulary to describe processes, for instance, “stouking” for attaching handles to pots, “setting” for placing the pots into the kilns to fire and “drawing” for taking the fired pots out of the kiln. Could these phrases have been a legacy of Joseph Bradshaw?

Joseph died at the age of 76 in 1812, which was a ripe old age for a potter at this time, especially for a potter working with a lead glaze. Joseph Bradshaw outlived Josiah Wedgwood by 17 years. Both men came from a similar background, both were dedicated to pottery, arguably with very different outcomes and achievements but none the less interesting lives.

Joseph passed on the pottery to his son, Robert Bradshaw. Robert worked the pottery with his brother Joseph (2) Bradshaw until 1822 when Robert died. Joseph (2) inherited one sixth of the pottery alongside Roberts’s children. Joseph (2) continued working the pottery with his son Thomas under a lease. Interestingly it looks like the potters diversified at this time and took on rope making as well as making pottery;

“Lease for a year. Dwelling house, called Bridge End House, with cow house, stable, pot kiln. Warehouses and other buildings, garden and orchard thereunto belonging. Also all those two workshops and warehouses now used for the purpose of carrying on the business of freckling and twine spinning together with a piece or parcel of ground now used as a ropewalk all which said premises are situated standing and being at Bridge End in the parish of Bentham and now in the possession of Joseph Bradshaw, yeoman” (from the deeds of Bridge End Cottage)

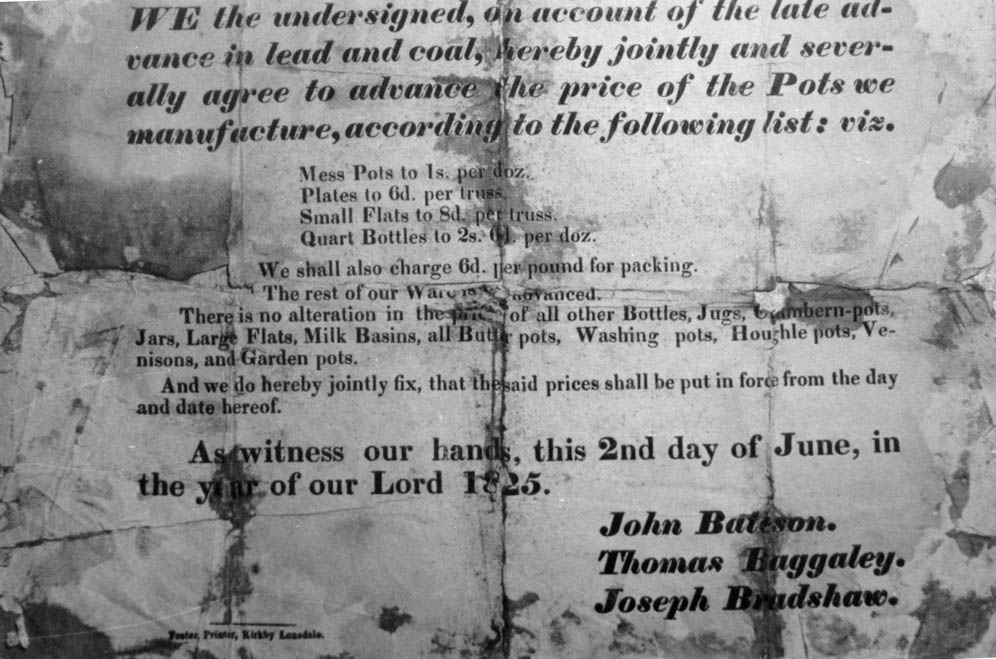

There was something of a cost of living crisis in 1825, caused by increases in the price of coal and lead that brought the three main earthenware manufacturers of Burton together to fix prices for certain wares. A document was drafted for this purpose. Joseph (2) Bradshaw’s name is included alongside John Bateson (Town End Pottery) and John Baggaley (Baggaley pottery).

On 3rd September 1835 Joseph’s (2) son Thomas Bradshaw bought Bridge End Pottery for the sum of £290. Thomas died in 1840, whereupon his brother John leased the pottery before taking on the mortgage for it on 12th August 1867. John Bradshaw then worked the pottery with his brother Benjamin Bradshaw.

The pottery left the Bradshaw family when it was sold on 31st December 1885. It was bought by Thomas Coates from the Baggeley Pottery on the opposite side of the river to Bridge End Pottery for the sum of £150. Thomas Coates immediately closed it as a pottery. This was probably a strategic step by Thomas to eliminate competition. Thomas converted the pottery into three cottages that still stand today. He sold the cottages in 1888 to Anne Eccles of Clifton Gloucester for the sum of £350.

I am grateful to Jane Burns for rekindling my interest in Bradshaw’s Pottery. Jane actually lives in one of the cottages that was formerly Bradshaw’s pottery and is an avid collector of Burton pots. Jane kindly provided me with the deeds of her house as source material for writing this. I have suggested to Jane that she should dig up the foundations of the pottery kiln, which should be all intact and buried in her back garden. Not only would this create an interesting and historic feature to her garden, but the digging would also reveal many shards of pots, all of which could be attributed to the Bradshaw family. You never know there might be an intact puzzle jug buried there! Alas, thus far my suggestion has fallen on deaf ears. I will keep trying.

Lee Cartledge, Bentham Pottery 2022

If you are interested in learning more about the history of Burton-in-Lonsdale and particularly the pottery industry, then you may be interested in the recently published “The Last Potter of Black Burton”, written by Lee Cartledge of Bentham Pottery. The book is available for purchase at the pottery (where you can get a signed copy), or on Amazon at (https://amzn.to/2VVHDzL)

The author has also put together a 4.5 mile walking guide around the sites of the former potteries of Burton, which is available here; https://www.benthampottery.com/burton-pottery-walk/