Burton-in-Lonsdale Pottery Walking Tour (Or if you are a kid “The boring pottery walk that my parents forced me to do”)

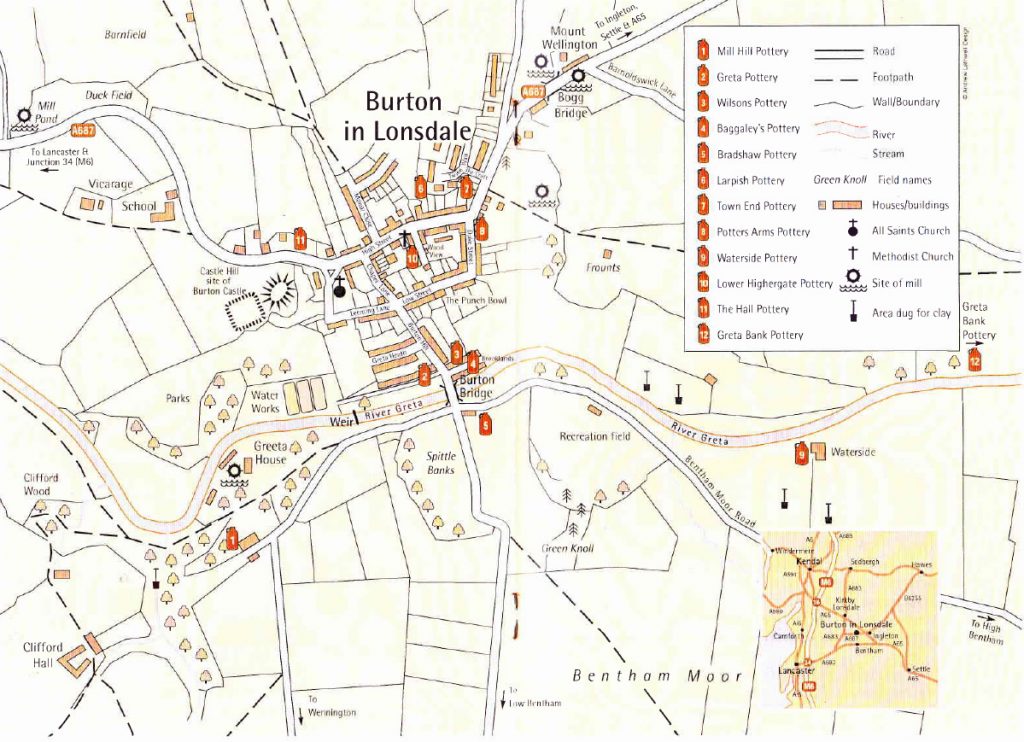

To celebrate the release of my recent book “The Last Potter of Black Burton”, I’ve decided to produce a walking guide tour of the some of the potteries of Burton-in-Lonsdale, so you can see the sites that are mentioned in the book. The walk lasts about 4.5 miles in total.

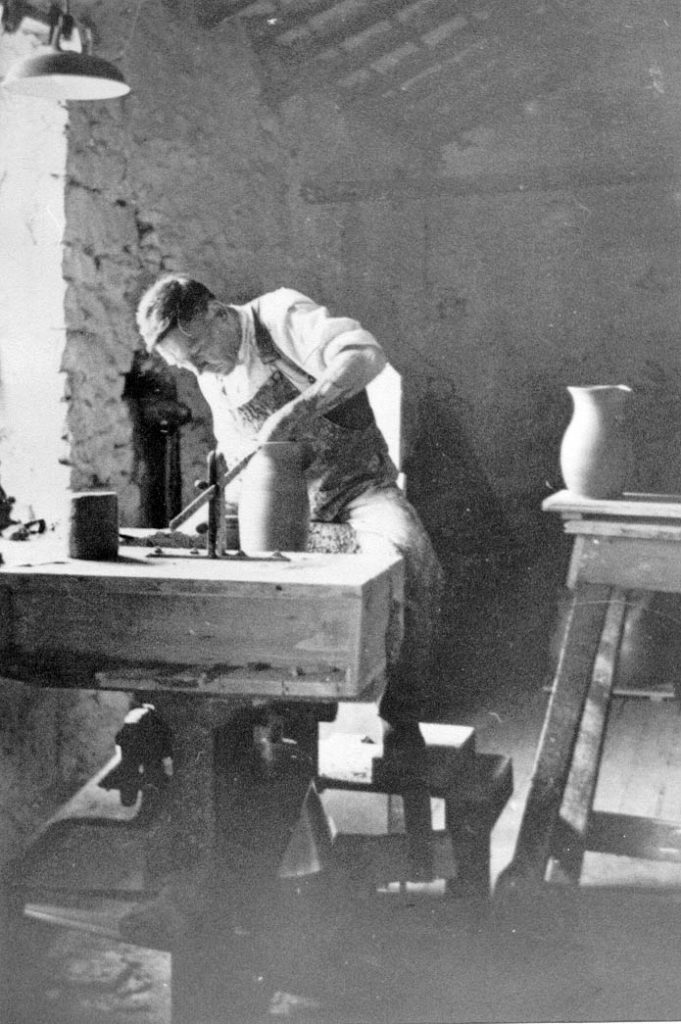

“The Last Potter of Black Burton” is the story of Richard Bateson, who began work at his father’s pottery at the age of 13 in 1907 and went on to run the very last of the Burton potteries, Waterside Pottery, which finally closed its doors in 1944. Richard’s career didn’t end there though, as due to a strange twist of fate caused in no small part by the Second World War, he went on at the age of 53 to teach pottery at the Royal College of Art in London.

“The Last Potter of Black Burton” is available for purchase at Bentham Pottery (I’ll even sign it for you if you visit me there.)

Unfortunately little remains of the pottery buildings, kilns and clay processing equipment of Burton, so I’m going to provide plenty of photos and you might have to use a little imagination. Initially I was going to release this as a printable A4 sheet, but I quickly realised I would need way too many photos and descriptions, so the best way to do this walk is with a mobile phone or ideally a tablet computer with this webpage saved. (Alternatively you can email me on lee@benthampottery.com and I can send you a pdf file of the walk.)

The walk begins at the bridge over the River Greta in Burton. There is a small space for parking on the Low Bentham side of the bridge but if that is full then take the right (if facing Burton) and park on the left, just beyond the riverside picnic area opposite the bowling green.

Potteries around the bridge

Okay here we go…

Starting from Burton bridge:

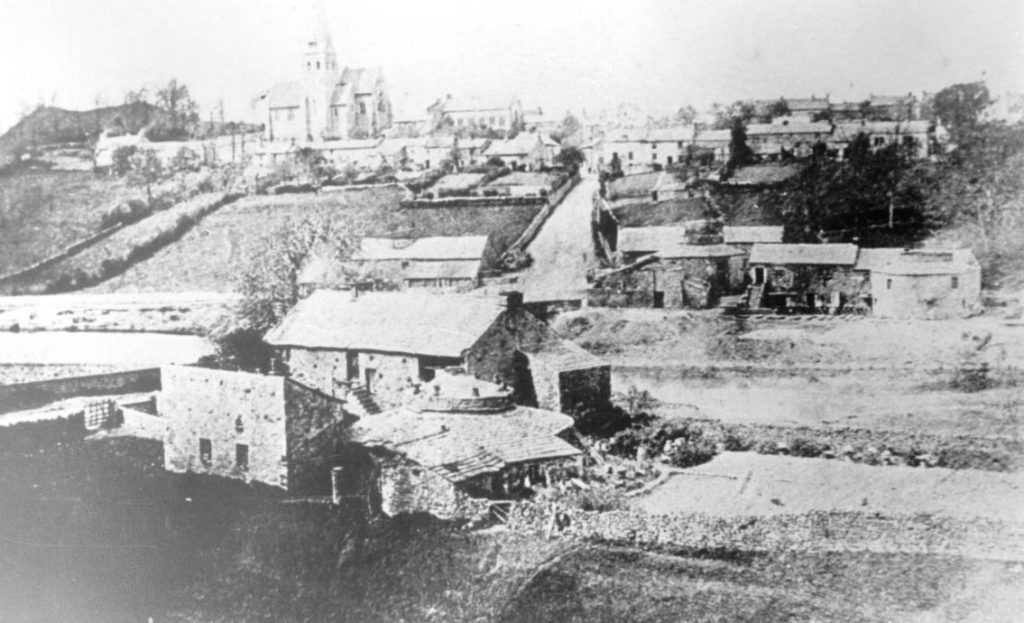

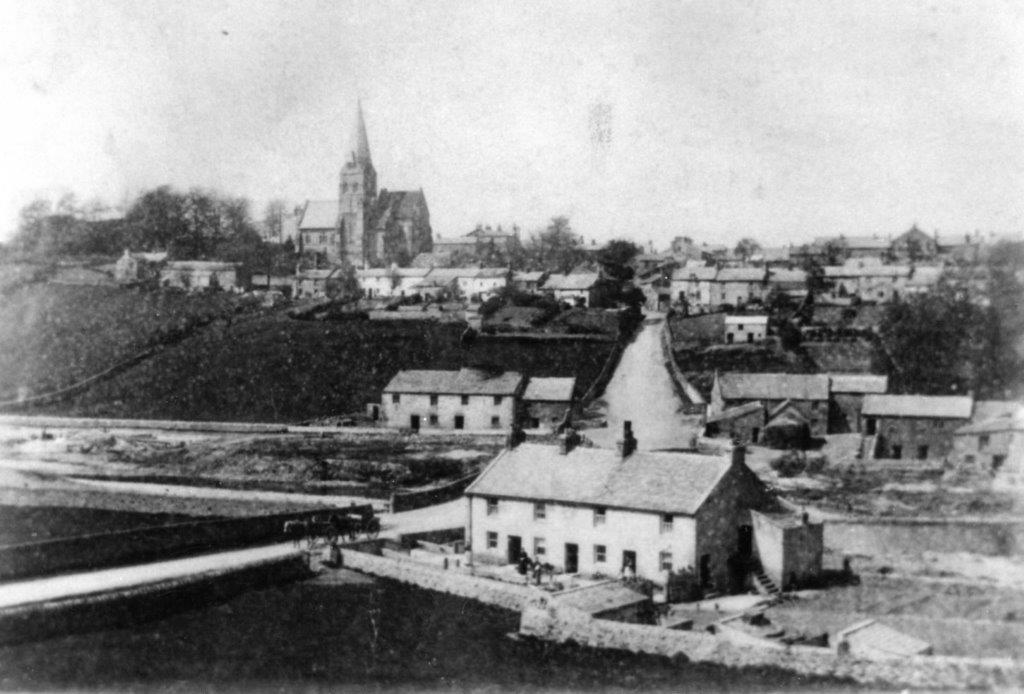

If you stay on the Low Bentham side of the Greta and walk back up the hill a bit and look back at Burton, you should get the following view:

The following photos and one drawing are of the same view, but on different dates;

The Burton “Blackware”

Next, we are going to visit the main source of terracotta clay, used by all the Burton potteries.

Walk back down the hill and before the bridge, turn left onto the lane to follow the river. After a short distance turn right onto a footpath signposted “Greta Wood”. The banking that forms on the left of the path was the original source of terracotta for the potteries and was affectionately known as “the good stuff”. Digging of “the good stuff” had to stop though, as a boundary wall was encountered and also further digging was in danger of undermining the road. Continue following the path past Greeta House. Greeta House was once the site of Greeta Cotton Mill. I realise that this isn’t pottery related, but Greeta Cotton Mill does feature in a tale later in the walk.

After you have passed Greeta House, it is worth looking at your feet as you walk because the potters made this track in order to access the clay that lay further on; and they used broken terracotta pots, as hard-core. You can find potters’ fingerprints in coils of clay that they would have used for separating pots in the kilns (look for the terracotta dots on the ground). A few minutes after Greeta House you will come to a small stone bridge over a stream. Do not go over the bridge, instead turn sharp left here. Continue along the track where you may notice a steep shale bank on your left hand side. This banking is the Burton terracotta clay. The shale looks and feels nothing like clay. It only gains the properties of clay when it is processed.

The Burton clay is jet black after being prepared for throwing, which is an unusual colour for clay. The Burton Potters referred to it as “blackware”. I have been told that it is black because it has a high oil content, which possibly provides “free” fuel during the firing process? I have wondered if the old name for Burton,” Black Burton”, originated because of the colour of the clay? The clay throws well on a pottery wheel. You can throw it really thin and produce complex overhanging shapes with ease. The clay fires terracotta colour.

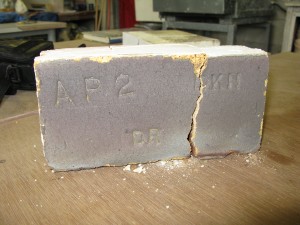

Apparently, below the shale and separated by a band of rock, is a seam of fireclay, which was used by the potters for repairing kilns and making firebricks.

Walk about half way up the hill where you may notice a small rockface. This is the last place where clay digging took place within the Wood.

Waterside Pottery and the disappearing river tale

Now retrace your steps back to the start of the walk. Cross the road to take the lane signposted to High Bentham and Ingleton keeping the river on your left hand side. We are now going to walk to the entrance of the former site of Waterside Pottery, where Richard spent much of his working life.

After a short distance on the left hand side in-between the road and the river just after the picnic area and orchard, you may notice the following:

The concrete cap covers a mine ventilation shaft, a number of these shafts were sunk in the vicinity. One of these mine shafts (possibly this one? Henry Bateson (Richard Bateson’s son), thought it was this one) features in the following tale which has been taken from Richard’s own memoir written sometime in the 1970s:

In the late 1860s, workmen on their way to their jobs at the Waterside Pottery and the hands who worked at the Greta Cotton Mill found that there was little or no water running from above Burton Bridge. The water which drove the large mill wheel and machinery ceased to flow. Imagine the consternation of the fifty or sixty workers from Burton, Bentham and district.

“T’ beck‘s dry!” would go round the whole district.

I think it was the Towlers, who had taken over from the Smitties, who were working the mill at that time, and of course were mainly responsible for the upkeep of the weir which used to be some fifty yards below the bridge.

After investigation, it was found that a large hole had formed in the river bed, about three hundred yards upstream, into which practically all the water was disappearing.

Now as to the hole appearing in the river-bed – the explanation was very simple. In the early eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Hodgsons and Sargentsons who owned the mineral rights had decided to sink a new coal shaft at Wilson Wood (just below Ingleton), but they were afraid of water that might enter from old workings. They decided to drain these old workings. To do this, and to arrive at an adequate lead to drain the water, they had to start over a mile downstream, in the entrance to Clifford Woods. Part of the level had to be run beneath the river – and it was here, at George Hole, that the water was disappearing.

Tom Baggaley Coates, who owned the Baggaley Pottery (Bridge End Pottery), came to the rescue. He blocked up the level by ramming down into one of the level-shaft some bales of cotton from the mill.

At approximately every two to three hundred yards, a shaft was sunk into the level, partly for air, and also to wind out spare soil or clay. The first air hole was in the field beyond Greta Pottery. This was the one that was blocked by T.B.Coates to enable water to flow into its proper course and bank up at the weir to turn the wheel at Greta Cotton Mill.

Keep walking along the road, past the playing field on your right hand side and a little after the children’s play area you will come to a drive way on your left hand side. This was the driveway to Waterside Pottery. Unfortunately you can go no further than this, as the driveway is on private land. The row of houses that was once Waterside Pottery is at the end of the drive, although not visible from here.

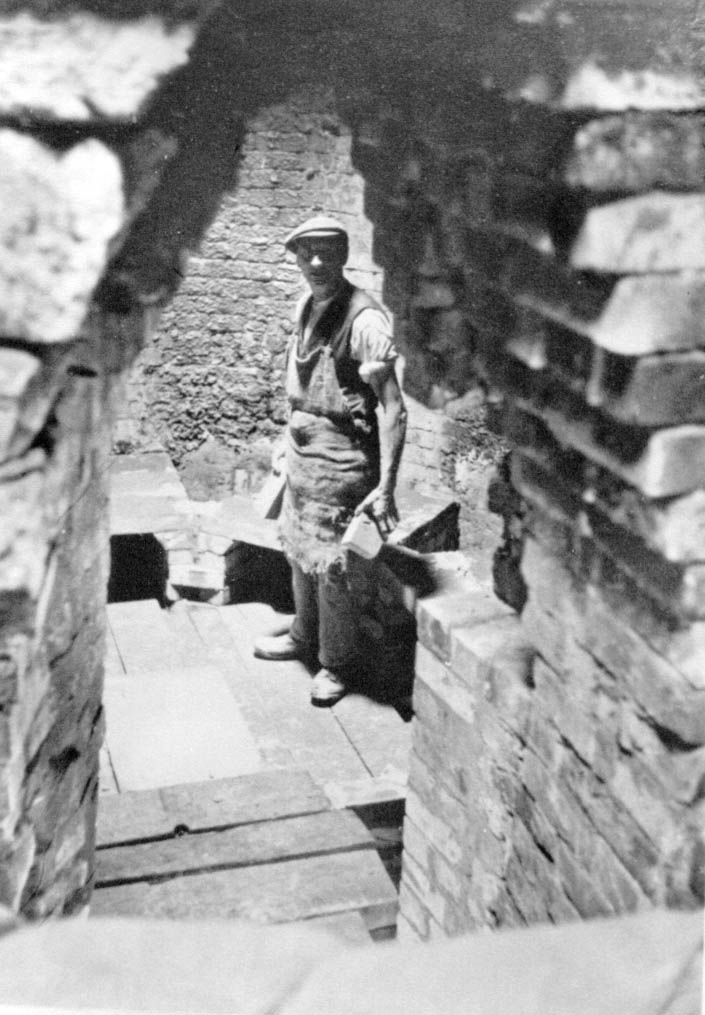

The reason for the location of Waterside Pottery is because it originally had opencast stoneware clay and coal in the field adjacent to the pottery. I’m not sure when the coal ran out, but the clay ran out in 1905. This forced the potters to dig a drift mine into the side of the hill to access more clay.

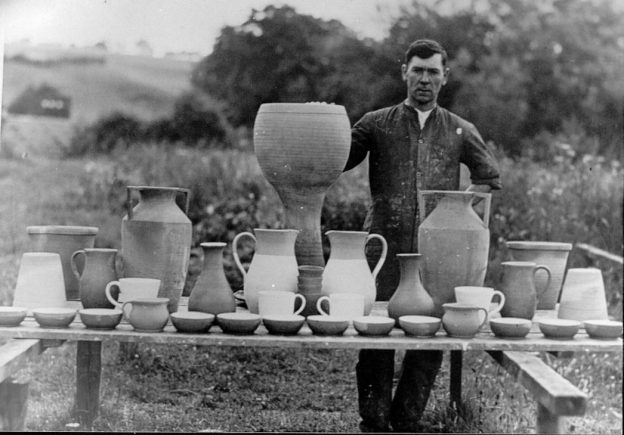

Here are some photos of Waterside Pottery as it was:

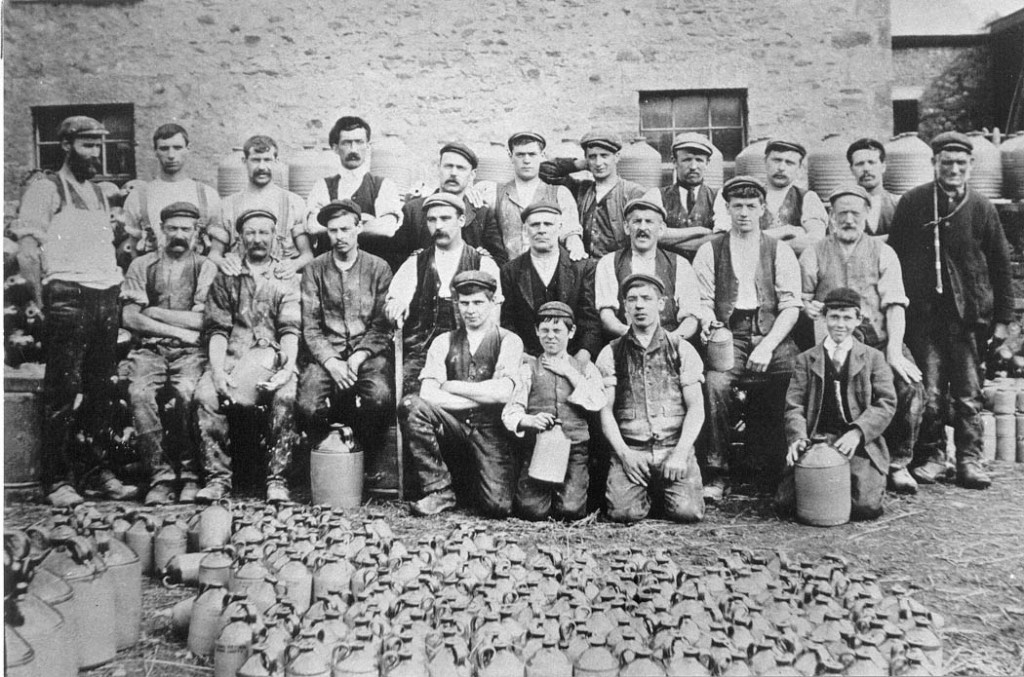

Back row: (left to right) Harry Bateson (thrower and owner), Charlie Armer (general worker, night fireman), Jack Fisher (bench hand, day fireman), Bill Fletcher (carter), Jack Lee (wand weaver), Isaac Briscoe (general worker), Arthur Baines (packer), Ted Jones (miner), Sep Lee (thrower), John B Brayshaw (namer and kiln loader), Jack Fletcher (carter). Middle row: (left to right) Bill Standing (fettler and kiln loader), Sam Skeats (engine driver), Jim Brayshaw (jnr) (turner, day fireman), Squire Taylor (wand weaver mainly, but could do any job in the pottery), Jim Brayshaw (snr) (wand weaver), Teddy Tomlinson (miner), Christopher Isaac Briscoe (naming, kiln loader, night fireman), Dixon Bateson (general worker). Front row: (left to right) Charlie Brayshaw (bench hand, taker off), Richard T Bateson (this was the year before Richard began work), Gordon Taylor (general worker), Harold Bateson (jam jar maker). Richard Bateson is in the front row with his hand covering his neck. Apparently he’d broken his top button and didn’t want his Mum to see it in this Lancaster Guardian photograph. Where was Frank Bateson on this day?

Before you leave the driveway, here is a tale from Richard’s memoir which took place very close to where you are now standing:

We had four horses – two Clydesdales and two Shires: Prince, a dappled grey; Polly, a large light brown; Star, a dark one with a white patch on its forehead; and the other whose name I can’t remember. One of them was always being rested while the other three were working.

Prince must have been in the family for many years. Before the enlargement of the pottery in 1900, only one horse had been needed. After that, trade seemed to be on the increase. Whenever Prince, the dappled grey, was mentioned by the carters or by one of the bosses, one could always sense a note of respect and reverence.

I have previously mentioned the settling-pens at the entrance to the Pottery road, at the Skipton Gate end. There was an old engine – which I fancy that I can remember one upon a time working. The enlarged pottery with its new additions was fitted up-to-date with a modern, more powerful engine – one would call it a two-stroke. The old stable engine had to be scrapped for old iron.

I was then about seven years old. Billy Kirkbride, the joiner, had the job of moving it. There was only room for one horse to move it from the place where it had lain for years – and that horse was Prince. Engines of the driving-power type in those days had large five-foot wheels attached to them. I can well remember the conversation between the men on the job.

“It’ll nivver do it,” says one.

“Thee hodd thy noise. Tha doesn’t know that horse,” said old Jack Fletcher the carter.

There was a man at each wheel.

“Now,” said Jack, “when I say ‘Go,’ push and push like buggery….”

There I was with my eyes popping – and probably using the same swear-words. I watched the great horse straining, and slowly one foot began to move, and then the other.

“She’s moving!” shouts Billy Kirkbride. “Push and push like hell! – and gradually the engine and boiler came out of its resting-place. Today, after almost eighty years, the spot still shows – and some of the clay pans are still to be seen.

Bridge End Pottery (Baggaley’s Pottery)

Again, retrace your steps to return to Burton Bridge and this time cross the bridge. Immediately after, you will see the following cul-de-sac on your right:

This is where Bridge End Pottery once stood. Bridge End Pottery was also known, at various times, as the Baggaley Pottery and the Coates Pottery. Here are a few photos of it:

Greta Pottery

If you look on the left hand side of the road. You will see the following building:

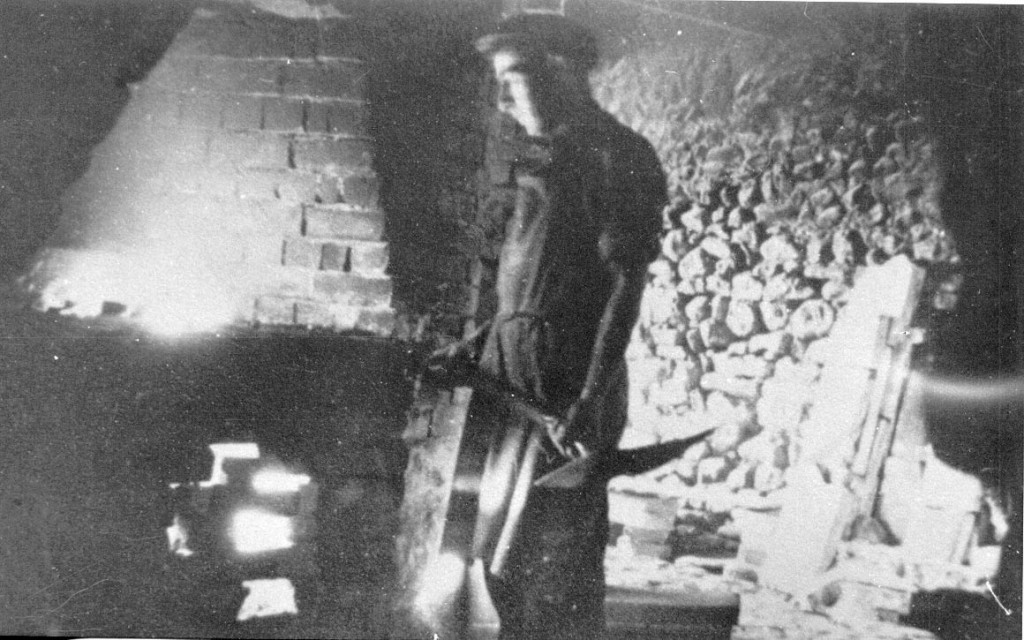

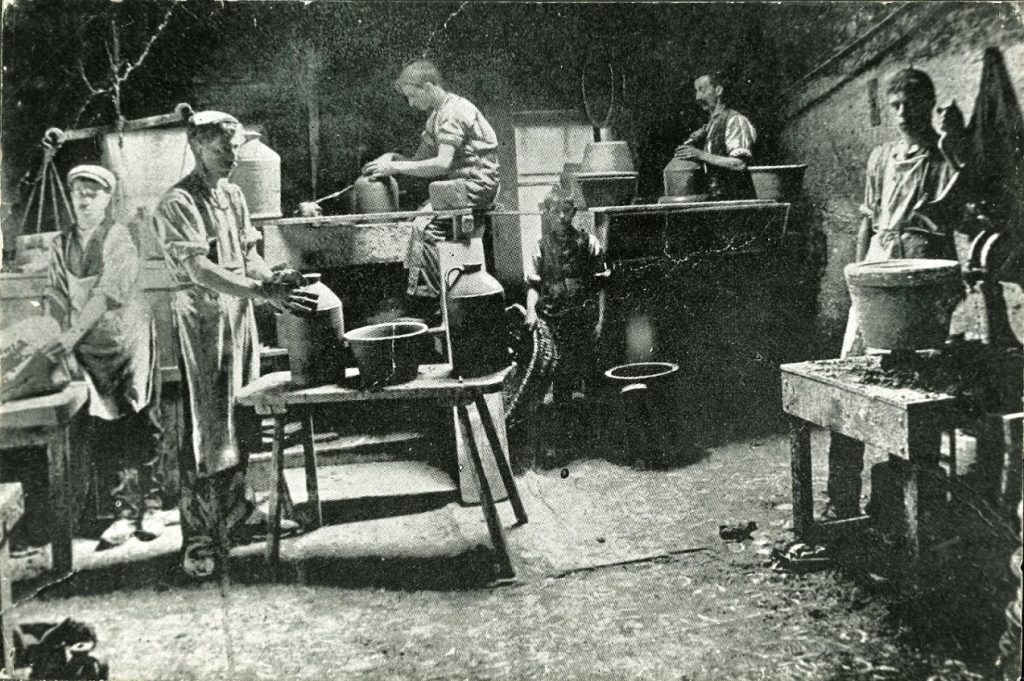

This is where Greta Pottery used to be. Here is a photo of the workers inside Greta Pottery:

Town End Pottery and Greta Bank Pottery

Now go up the steep hill into Burton and turn right onto High Street. It might be worth calling into the community shop for a quick sandwich and coffee (on the left hand side), because you’re going to need some sustenance for the next section!

Carry on along High Street pass the entrance of Duke Street after which the road bears left. Soon after this, if you have a close look at the wall you may well see the following:

I’ve heard people say that this is a plague bowl, for washing money in. However another theory (put to me by Henry Bateson, Richard’s son) is that it was more likely to be the mortar of a pestle and mortar set , that may well have been used at Town End Pottery for grinding glaze ingredients.

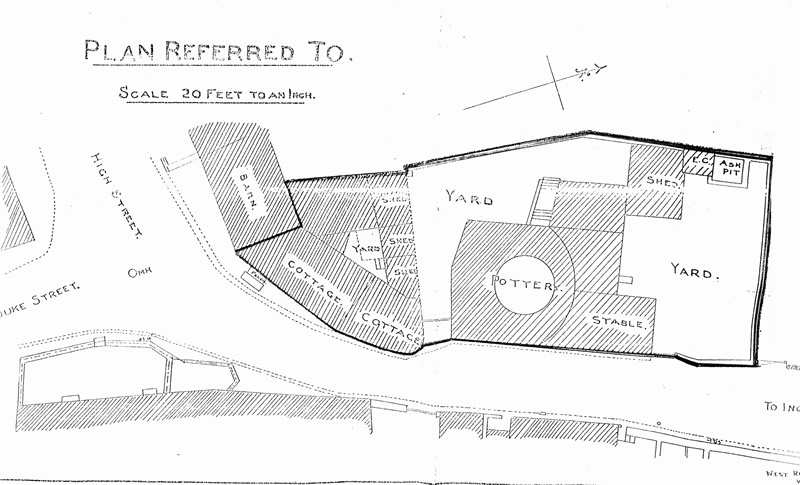

Now look out for “The Croft” street sign on the left hand side, shortly after this bend in the road.This is roughly where Town End Pottery used to be. Regretably I have yet to find a photo of Town End Pottery, which is frustrating, as it was still in business up to the First World War. Somebody out there must have a photo of it? The only image I have of Town End Pottery is on the following drawing, where you can see the bottle kiln at the top right of the picture:

I have a plan of Town End Pottery, but its not as good as seeing an actual photo of it. Although it does give you a good idea of where it was.

Greta Bank Pottery

You’ve got two options for the next part, you can take the footpath on the right next to the bus stop (opposite where the stone mortar/plague bowl is), or if the weather has been wet (the footpath involves walking through fields), you can carry on down the road (heading towards Ingleton) and take the next right down a single track lane (Barnoldswick Lane).

If you take the footpath option, the path starts off very well defined, but it suddenely deposits you through a small metal gate into an open field with a derelict barn in front of you and no obvious way on. Basically head to the left of the barn towards a gate in the field. Keep going through another 4 fields until you encounter a footpath sign and stile in the wall on the left. Cross the stile and turn right and you will be in Barnoldswick Lane. Turn right here.

Walk to the very end of Barnoldswick Lane, turning right around the bend to avoid a drive way on your left named Brentwood Farm.. This brings you very close to the River Greta. After a few houses, the furthest house on your left, Lower Greta Bank House, is where Greta Bank Pottery used to be.

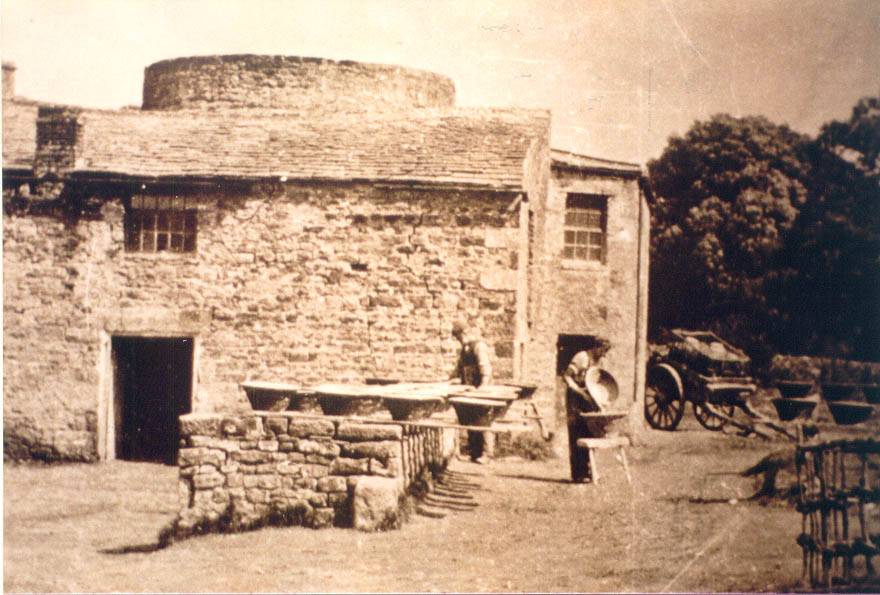

Here is a photo of it in its prime, with a smoking kiln:

If you look up the first drive of Lower Greta Bank House there is a low curved wall with two openings just to the right of the drive. This is a small section of what was the outside wall of the kiln. It really is the last physical remnant of the Burton potteries past (in terms of buildings anyway). Please be aware that this is in a private garden, so only view it from the road.

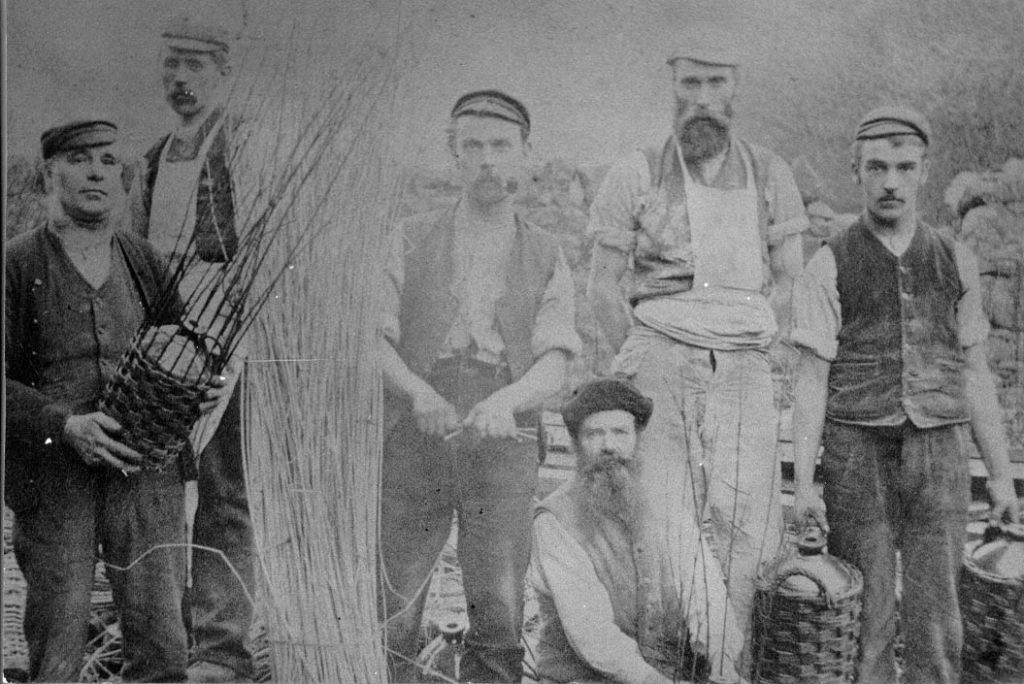

Up to the 1930s you would have been able to continue along Barnoldswick Lane over the River Greta via Greta Bank Bridge, or Penny Bridge as it was known. Squire Taylor, the basket maker from Waterside Pottery, lived at the toll house for Penny Bridge. Apparently he wisely invested all the takings from people crossing in Guinness bought over the bar at the Joiners Arms in Burton. During the 1930s great depression, the good folks of Burton discovered a source of free coal in the river bed around the bridge. Removal of large quantities of this coal resulted in the bridge and banking being undermined and the river took the bridge foundations. It eventually also took Squire’s house. The bridge was never rebuilt.

Now returns to the mortar/plague bowl location on the High Street, either by the road or by the footpath through the fields.

The Punch Bowl and the Graveyard Challenge

Turn left down Duke Street then sharp right to arrive at Low Street. On the corner of Duke Street and Low Street you will find Bleaberry House on the left hand side. This is where Harry Bateson of Waterside Pottery lived and it is where Richard Bateson grew up and ran away to the First World War from.

Half way down Low Street the Punch Bowl Inn is on your left. It would be foolish not to go inside and have a swift drink. You’re definitely going to need some fortification for the next bit. Whilst enjoying your chosen beverage (spirits might be the best choice), mull over the fact that The Punch Bowl Inn used to be owned by the Baggaley family from Bridge End Pottery and they used to craftily pay the pottery workers over the bar on a Friday night.

And so on to the last part of the tour, the Graveyard Challenge. Turn left outside the Punchbowl, go straight across the road onto Leeming lane and follow the lane around to the right. This leads to the church. Head into the graveyard and see how many potters you can spot on the gravestones. Good pottery surnames to look for are Bateson, Baggaley, Bradshaw, Brayshaw, Briscoe, basically anything beginning with B. Actually that’s not really true, here are a few more: Kilburn, Coates, Parker and Taylor. Some of the main characters from my book can be found buried here; these include Henry (Harry) Bateson, Richard Bateson, Frank Bateson and Robert Bateson. Two gravestones mention actual potteries. I came to the sad realisation whilst researching this that I knew more dead people in Burton than live ones!

This walking tour has looked at the five potteries that were still in production up to the First World War; namely: Waterside Pottery, Bridge End Pottery, Greta Pottery, Greta Bank Pottery and Town End Pottery. There were at least 10 other potteries operating at different times in the past. The following map will give you some idea of their location:

Please feel free to contact me and let me know how you got on with this walking tour. I’d be interested to know if you think I should add anything else, or even omit anything. I’d be absolutely delighted if anybody can show me any photos of Town End Pottery, or any other Burton pottery for that matter.

All that now remains is a short car journey to Bentham Pottery (head towards Low Bentham from Burton and you’ll find us on the right after the cross roads), where you can purchase “The Last Potter of Black Burton”. I’ll sign it and even give you a tour of the pottery. We’re open Monday to Friday, some Saturday afternoons, but not Sundays.