The Men of Greta Pottery,

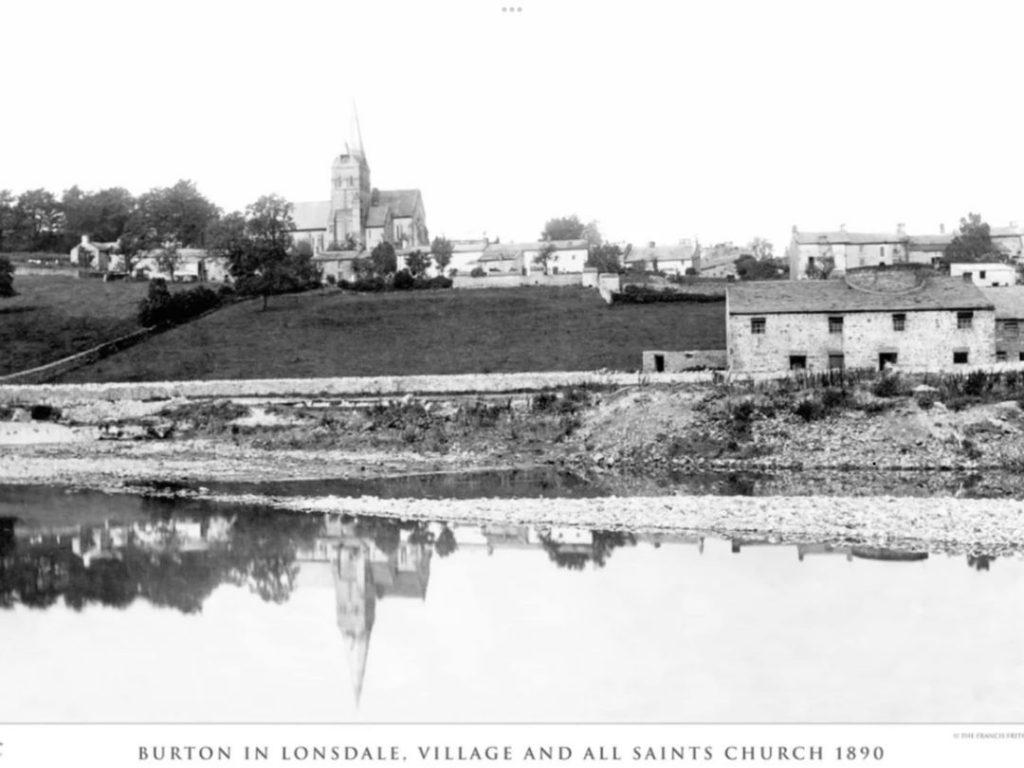

Burton in Lonsdale

By Lee Cartledge, Bentham Pottery 2024

.

Introduction

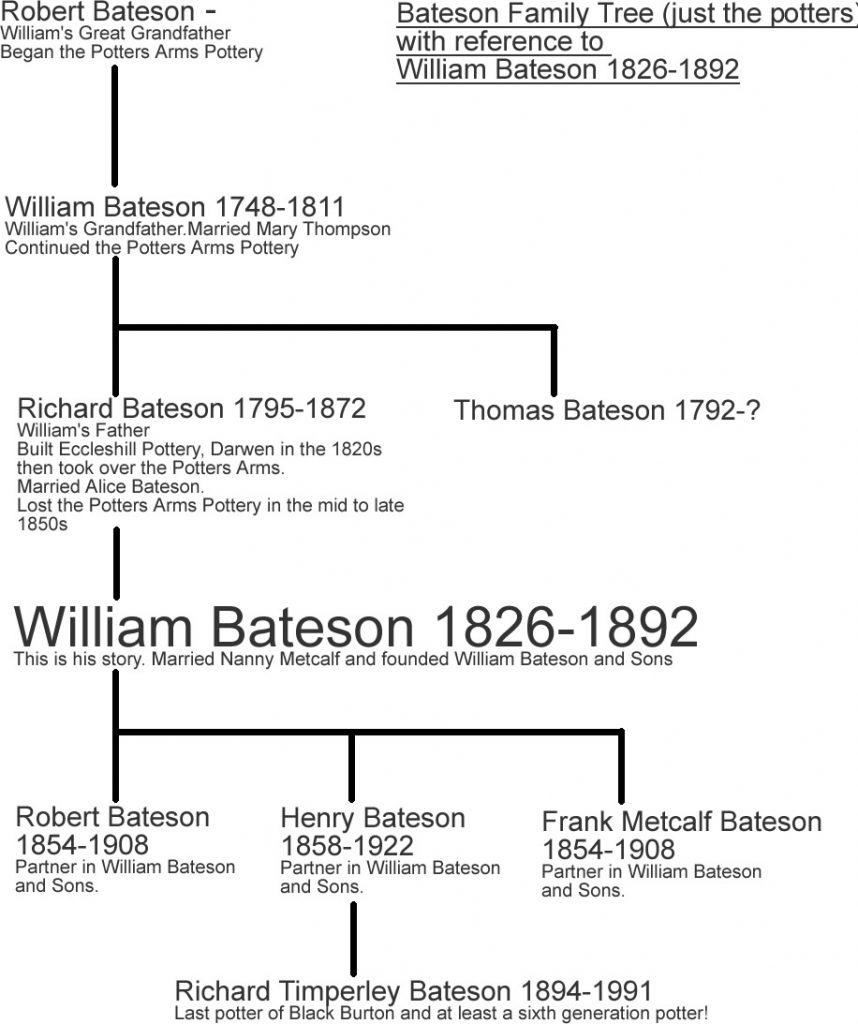

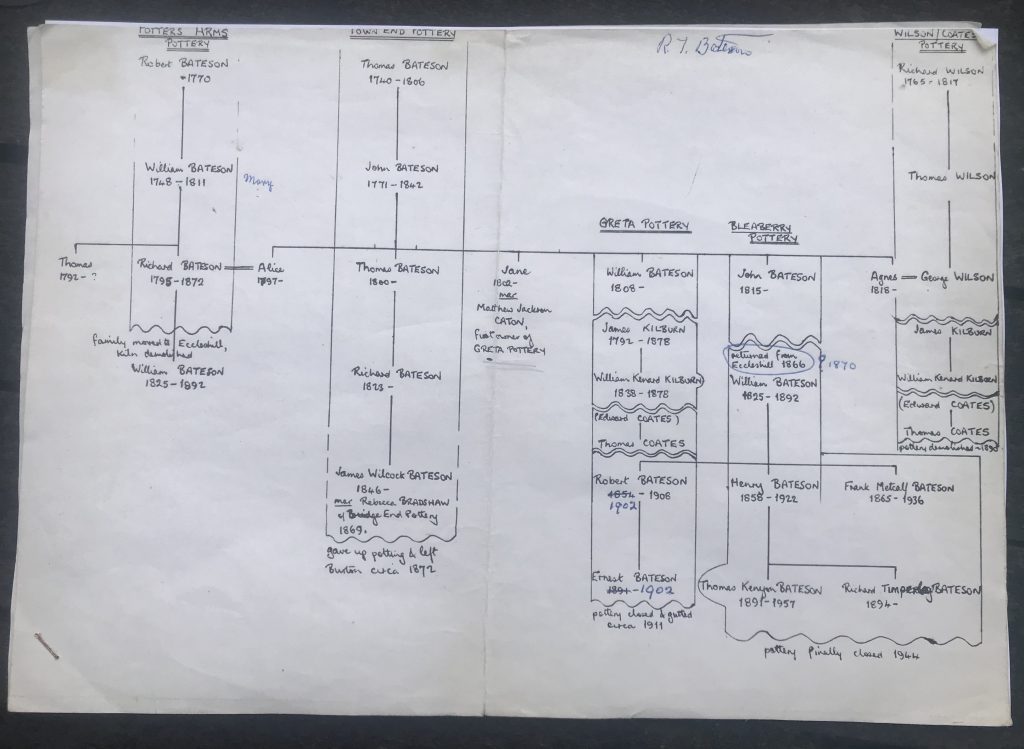

In the late 1980s, Richard Timperley Bateson (RTB) the very last of the potters of Burton-in-Lonsdale, gave me a hand drawn family tree of the Bateson family. The family tree had a Jane Bateson born 1802, with a note next to it, “Married Matthew Jackson Caton, first owner of Greta Pottery”. Now, despite thinking of myself as something of a Burton-in-Lonsdale pottery historian, I had never heard of Matthew Jackson Caton with respect to Greta Pottery or any other Burton pottery for that matter. I checked the pottery history books and it turns out that neither had anybody else. Matthew Jackson Caton seems to be absent from all records. It was this more than anything that was the catalyst for me writing this essay.

I would like to say at the beginning that this has been very much a combined effort. It is true that I, (Lee Cartledge) have written it, but left unaided it would be full of large gaps and uncertainties in the timeline, which I would have attempted to fill with guesswork, speculation and waffle. I have been very fortunate therefore to have Julie Gabriel-Clarke of the Burton in Lonsdale Heritage Group providing the research and effectively rendering these gaps with hard evidence and facts. In short I couldn’t have done anywhere near as detailed a job without Julie’s hard work.

Being a potter myself, I have always been intrigued by Greta Pottery as this was the very first stoneware pottery in Burton-in-Lonsdale. Historical accounts dismiss this move to stoneware in one sentence as though it was a simple thing to do. The move to stoneware would have been a huge step for the Burton potters to undertake in the 1830s.

Prior to Greta Pottery all the potteries of Burton produced earthenware usually with a lead glaze.

Stoneware has a number of advantages over earthenware: it is denser and much more durable and the clay actually vitrifies in the firing, making it totally impermeable to liquids including acids (earthenware is rarely completely impermeable). These factors make it ideally suitable as a material for making bottles for storing liquids.

To manufacture stoneware the Burton potters had to do the following:

- Find useable stoneware clay in the area with rights to dig it. Stoneware fires 200 degrees higher than earthenware at a temperature of 1250-1280 degrees. Earthenware would melt or bloat (form bubbles in the walls of the pot) at that temperature and I have painfully experienced it in my kilns. So my question is: how do you check you have found stoneware clay when the only kilns in the village fire to the lower earthenware temperatures?

- Implement a new kiln design to achieve a stoneware temperature using higher temperature refractory bricks. Earthenware kilns are ‘through draft’, meaning the firebox leads straight to the firing chamber with the flu coming out of the top. Heat literally passes through the kiln. To achieve stoneware temperatures a ‘down draught’ kiln is required, where the exit flu is at the bottom of the kiln which forces the heat to build up in the firing chamber thus achieving the higher temperature. Where did the Burton potters learn to build such a stoneware kiln?

- Formulate a stoneware glaze. Stoneware glazes are very different to earthenware glazes as they use feldspars to flux the glaze instead of lead. Lead actually combusts at stoneware temperatures. An experimental period would have had to ensue in order to get the right balance of glaze ingredients to fit the Burton stoneware clay body without the glaze crazing or peeling off. How did the Burton potters achieve this?

- Most importantly, find a market for stoneware pottery. There would have to be a strong demand for stoneware pottery in order to justify doing the three things above. This is the only requirement I can answer with any confidence. From the early 19th century there was an increased demand for stoneware bottles. The Burton potters must have seen that this was where the market was going and they decided to jump on the bandwagon. Greta Pottery was set up as a stoneware bottle manufacturer.

I think without doubt that there must have been an outside influence to enable the transition to stoneware. Perhaps they brought in somebody with specialised knowledge from out of the area to help with this. Members of the Bateson family had opened potteries in Darwen and Castleford and possibly even Stoke-on-Trent. Perhaps one of these potters had learnt the stoneware techniques and was able to bring them back to the village.

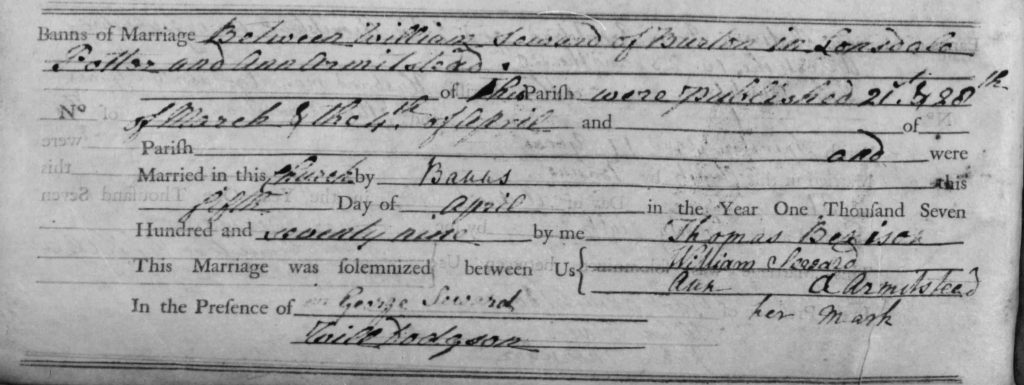

Greta Pottery was set up around 1830 by two men in a partnership: William Bateson and Matthew Jackson Caton.

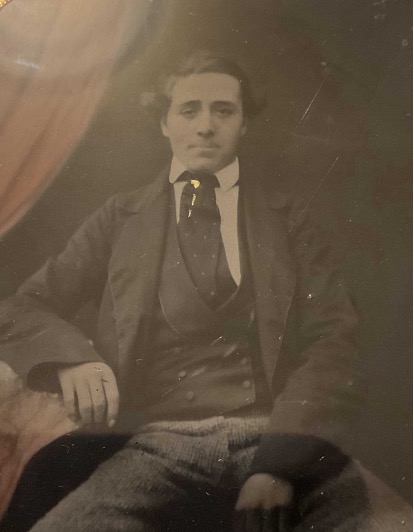

William Bateson (1808-1885) – ran Greta Pottery c1830-c1848

William Bateson was born 1808 the son of John Bateson (1771-1842) and Ellen Bateson (1775-1852) (nee Fawcett) of Town End Pottery, Burton-in-Lonsdale. William would have learnt his craft from his father at Town End Pottery. The following description of William is from the Dalesman magazine of 1949:

John’s son William married in 1834, and seems to have built this pottery, which made stoneware; Grabham states that it was the first stoneware pottery in Burton and was worked by William in 1830.

William (“Old Willy”) seems to have been unsettled. He spent time as a soldier in India, but returned, and suffered from the ill-effects of sunstroke for the rest of his life, and is remembered as tottering down the street continually swaying his big head. “He had a thirst, too,” says another who remembers him. His sons James and Richard were strict tee-totallers” (Dalesman March 1949)

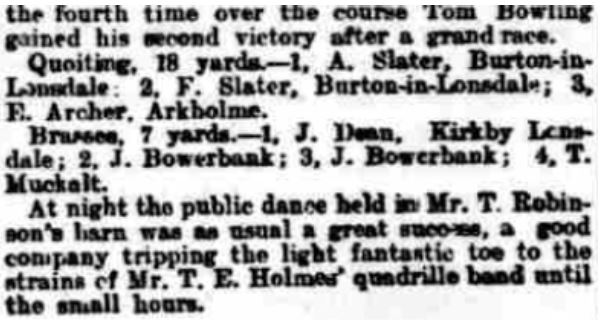

I have a couple of newspaper articles that refer to a William Bateson of Burton-in-Lonsdale from this time. I can’t prove conclusively that this is the potter William Bateson of Greta Pottery (It was common for members of the extensive Bateson family to name their sons William). The following article does sound very much like the man described in the Dalesman magazine though:

“THE ANCIENT ROYAL FISSERS.”

AT BURTON-IN-LONSDALE.

(To the Editor of the “Lancaster Standard.”) SIR-Your valuable issue has been sent to me here, of the 27th June last, which I have read with the greatest pleasure, and amongst the news of the Coronation festivities was the fine doings at my native village of Burton-in-Lonsdale, the King of the “Ancient Fissers” being one of the notable characters in the procession there. It is a long time ago, but my memory serves me so well that I remember their first president, who was one of the most noted and respected men in the village, Mr. William Bateson, otherwise best known as “Old Lame Billy.” It was he, my late lamented father, Messrs, Wm. Slater, Rawson, Kirkbride, and a few others who formed the order.

Their rules were very strict indeed-(1) No member must work until he sweat; if he did, fine 2s. 6d. (2) If a member was going along any road and met a horse, cart, or any other conveyance, he must not turn out of the way; it or they must make way, otherwise fine of 3d. If a member got on fire, he must not extinguish the flames himself; others must do it. Fine 10s. or be expelled at the option of the council. and so on. All fines paid must be spent in ALE, first at the Punch Bowl, and then in turns at every inn in the parish. I well remember the president going for a load of coal to the Ingleton Colliery, at Wilson Wood, New Winnings. This was in winter, and each one must take his turn according to pit laws. Billy had to wait several hours. A fire was burning on the pit bank, in what was called a fire pan. He lay down and dropped asleep, when, lo, a red hot cinder dropped out and fell upon poor Billy’s coat tail. This was seen by another man, who wakened the president by a shake and calling out, “Billy, yer afire.” Billy turned up his head (tall hat on, as usual), and said, “If I’se afire thow mun put me out. If I do I’s’al be fined 10s. by our Royal Fisser Club.” This occurrence was about 1859, and was told to me in 1862, when I visited Burton to see my old people, and after I had told them of my doings in London, and Dick Remington, of Ingleton, being under my charge there, at the Exhibition in Hyde Park.

I have heard of many things done by members in Burton and the district. One was a member was fined 5s. and could not pay. Well, he must be expelled then. “No,” said a member, “Let’s hang him if he can’t pay.” “All right, if ye gie me a quart o’ ale an let me sup it first yo may hang me after.” A rope was placed to a hook in the ceiling of the room, a quart was fetched for him, and rope placed round his neck ready. He mounted the table, drank his ale, and said “Ready,” when someone kicked the table from under him and let him drop some 6 inches. Black in the face he went, when one of the company took out his knife and cut the poor fellow down. “How did ye like hanging?” he was asked. “I didn’t like it, but I gat th’ale.” Such were the doings in those days. How they are now I have no idea, but as the old school must have gone, their rules may be altered, and I suppose they have no one left who has trained his cat to follow him to the church, wait in the porch until service was over, and then follow his master home, the same as I have seen “Lame Billy’s” do many times.

(George Barker, Cape Town, 31st July, 1902. This was published in the Lancaster Standard and County Advertiser 22 August 1902). Although the article was written in 1902 it is looking back to events in the 1850s. “Lame Billy” does sound like the man described as “tottering down the street” in the Dalesman article. Also the name “Fissers” sounds like a derogatory name for Officers, which an ex-army man could well have used?

The second article if nothing else proves that the concept of the autonomous vehicle is nothing new:

ASLEEP IN A CART.-William Bateson, a carrier, living at Burton-in-Lonsdale, was charged with being asleep whilst in charge of a horse and cart on the high road at Melling, on the 8th March -Defendant pleaded not guilty.-P.C. Moss, stationed at Cowan Bridge, said he saw the defendant on the highway at Melling at a quarter to eight on the evening of the 8th of March last. He was asleep in his cart, the reins being fastened on the horse’s back. Witness wakened him, and then the defendant drove on. The defendant was carrier from Lancaster to Burton-in- Lonsdale-Cross-examined by the defendant, witness said he walked about 100 yards by the side of the cart before he wakened defendant. Defendant said he was not asleep, he was laying down in the cart, but he had his hand over the reins and had full control over his horse.-The Bench fined the defendant 5s. and costs, 12s.

(Lancaster Gazette 05 April 1879. There is every possibility that this is William Bateson of Greta Pottery, as William had left the pottery industry by this date and had become a “Wooling Cloth Agent”, so he could have been carting wool.)

Matthew Jackson Caton (1782-1862) – owned Greta Pottery c1830-c1863

Matthew Jackson Caton was born 1782 to Richard Caton, a maltster from Lancaster and Alice Jackson from Warton. He owned land in Over Kellet, which I presume is where he made his money although I’ve no real idea what he did for a job in his early life, perhaps he inherited his wealth?

Matthew married William Bateson’s sister, Jane in 1835. This was Jane’s second marriage, her first husband Robert Hyman died in 1830. Matthew was 20 years older than Jane.

Marrying Jane was thus Matthews’s connection with Burton-in-Lonsdale and the potteries and, presumably, the young William Bateson.

Matthew provided the money to finance Greta Pottery and was the overall owner. Matthew would have embarked on his pottery journey in his early fifties (William by contrast would have been in his mid-20s).

William Bateson and Matthew Jackson Caton at Greta Pottery

My best guess is that the sequence of events went as follows:

William Bateson learnt the art of pottery at Town End Pottery under the guidance of his father, John Bateson. He escaped village life and joined the army for a few years eventually returning to Burton. He was probably never going to inherit Town End Pottery as he wasn’t the eldest son (his older brother Thomas worked with his Dad), so he had to make his own way in life. He possessed an entrepreneurial nature, a strong charisma, an ability to problem solve and, if indeed he was the king of the “Ancient Royal Fissers”, a capacity to drink vast amounts of ale. William realised there was a high demand for stoneware bottles, as Town End Pottery were possibly being constantly asked to make them. He saw a gap in the market and decided to do something about it. He used his family contacts in the pottery world to research stoneware manufacturing, sent samples of local clay to be fired in a stoneware kiln outside the area and obtained kiln designs and glaze recipes. The one thing he lacked was the funding required to build a pottery and this is where his brother in law (or his soon to be brother-in-law) Matthew Jackson Caton came in. I suspect Matthew also possessed similar qualities to William and saw this as a great business opportunity and it was also a way to cement his relationship with the whole Bateson family into which he had married.

A partnership “Bateson and Caton” was thus formed with William overseeing the running of the pottery and probably doing a lot of the throwing and Matthew as the owner and administrator.

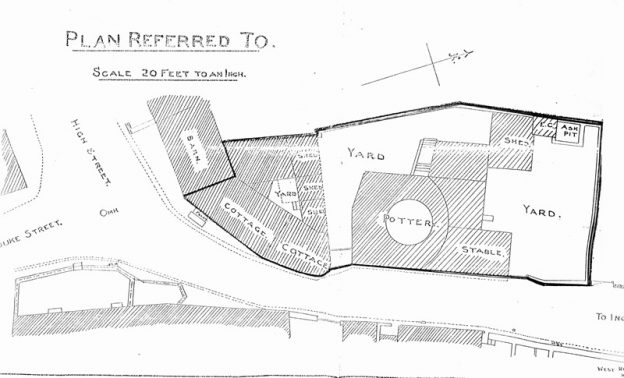

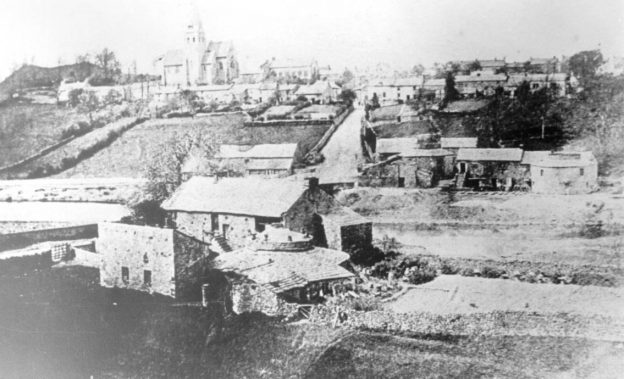

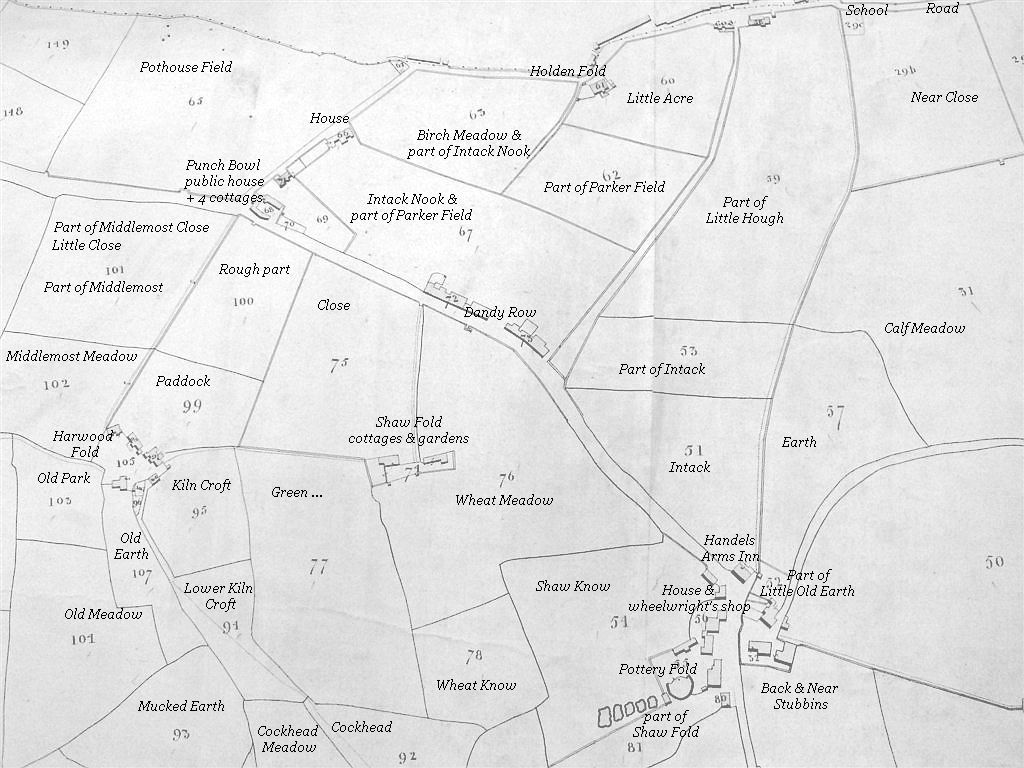

Greta Pottery would have been built sometime in the early 1830s and production commenced soon after. The stoneware clay was originally dug from near where the Burton football pitch is now.

Curiously the partnership only lasted a few years and was dissolved in 1837. I’m not sure what the reason was for this. Perhaps Matthew just didn’t like the dust, filth, slurry and smoke that are the reality of pottery manufacture, it really isn’t for everyone. Maybe the two men just didn’t “gel” together?

Notice is Hereby Given,

THAT the PARTNERSHIP heretofore subsisting between me, the undersigned, MATTHEW JACKSON CATON, and WILLIAM BATESON, carrying on Business under the Firm of BATESON and CATON, as STONE WARE MANUFACTURERS, at BURTON-IN-LONSDALE, in the West Riding of the County of York, is this day DISSOLVED. And all Persons from whom any Moneys or Effects are Due to the said late Firm, are hereby required NOT to PAY or DELIVER the SAME to the said WILLIAM BATESON, or any other Person, without my consent.

Dated the 10th day of August, 1837.

MATTHEW JACKSON CATON.

Witness to the signature of Matthew Jackson Caton, THOS. SWAINSON, Solicitor, Lancaster.

N.B. The Business will still be carried on at the Manufactory by Mr. MATTHEW JACKSON CATON.

(Westmorland Gazette 12 August 1837)

The above newspaper clip seems to imply that Matthew Jackson Caton was intending to continue the business as a sole trader. However what seems to have happened is that Matthew leased the pottery to William Bateson and William continued the business.

Matthew left Burton in 1840 and moved to the Fleetwood area. In 1842 he tried to sell Greta Pottery:

TO BE SOLD BY AUCTION,

BY MR. KILSHAW,

ALL that Newly Erected POT KILN, or STONE WARE MANUFACTORY, with the Warehouses, Outbuildings, Clayhouse, Fire Pan, and Appurtenances to the same belonging, situate and being at Burton-in-Lonsdale aforesaid, and now in the occupation of William Bateson, as Tenant thereof.

The Kiln is situate on the Banks of the River Greta, from which it receives a plentiful supply of water, and is possessed of every convenience for carrying on the above Business with advantage. It is also well accustomed, and has gained its present eminence by producing the best Stone Ware in this part of the country.

The Purchaser will be entitled to an unlimited right of getting excellent Clay suitable for the Trade, on an Allotment situate on Bentham Moor, and distant about a quarter of a mile from the Works. He will also have the same right over all the unenclosed Lands within the Township of Burton-in-Lonsdale aforesaid.

A plentiful supply of Coal, well adapted for burning Stone Ware, can also be had at a trifling expense, within a mile from the Manufactory.

The above Premises adjoin the High Road leading from Burton-in-Lonsdale to Bentham; are distant seven miles from the Market Town of Kirkby Lonsdale, and twelve from Lancaster.

The said WILLIAM BATESON will shew the Premises; and further particulars may be known by applying to Mr. MATTHEW JACKSON CATON, of Fleetwood, the Owner, or at the Offices of Messrs. W. R. and H. A. GREGG, Solicitors, Kirkby Lonsdale.

Kirkby Lonsdale, June 27, 1842.

(Westmorland Gazette 09 July 1842)

Unfortunately for Matthew the pottery didn’t sell, so William Bateson continued to lease it.

William’s brother John Bateson must have seen the potential of the stoneware bottle industry around this time, as he went on to build Bleaberry Pottery (later becoming Waterside Pottery), the second stoneware pottery in Burton. John then commenced producing stoneware bottles in direct competition to Greta Pottery.

I can only imagine this went down like a lead balloon with William and there is evidence of the brothers falling out. An actual letter from a Kirkby Lonsdale solicitor acting on behalf of William Bateson describing an incident and injury at a clay pit in Burton was bought by a friend of mine from eBay in 2020. The letter was then posted back to Burton 175 years after it first arrived in the village:

Kirkby Lonsdale

6 June 1845

Sir

We are instructed by William Bateson to commence legal proceedings against you for the damage and injury he has sustained in consequence of your having thrown a quantity of rubbish into the clay pit in his occupation at Burton-in-Lonsdale and we think it right to remind you that for a valuable consideration Mrs Redmayne has entered into an agreement with our client under which he had the right to get clay for a certain term. Unless therefore you desist from the conduct you have adopted and make our client a fair and reasonable compensation for the injury he has sustained and pay our charges for the letter within three days from this an action at law or such other proceedings as we may think proper will immediately after that time be taken against you. We are also instructed to require the immediate payment of the balance due from you to our client and inform you that if the amount is not paid by or before Wednesday the 11th instant a writ will be issued against you without further notice.

(6th June 1845 Mr John Bateson, letter from Messrs Gregg as to dispute with your Brother William. Letter sent from Messrs Gregg, Solicitor in Kirkby Lonsdale addressed to Mr John Bateson, Potter, Burton-in-Lonsdale regarding an injury his brother William received and damage caused to his clay pit by John Bateson. The letter was purchased on July 4th 2020 on eBay). With thanks to Jane Burns for letting me use it in this essay.

I’m not sure what the outcomes of these legal proceedings were. Hopefully William and John managed to patch things up ensuring happy, incident-free family get-togethers at Christmas.

Shortly after this clay pit incident, William decided to leave Burton and build or take over an existing pottery in Scotforth, near Lancaster. Was the rupture between the brothers the cause of this move, or was William just fed up of renting Greta Pottery and wanting his own works? He took quite a few Burtonians with him for this venture:

The 185l census shows William Bateson of Burton-in-Lonsdale at Scotforth, an “earthenware manufacturer employing six men”. Together with William’s three sons James (16), Richard (15) and John (13) we find Robert Rumney, pot maker and thrower’ and the brothers William and Christopher Batty all from Burton. Further examination of the Census return reveals a larger settlement of Burton émigrés in Scotforth in 1851 than perhaps has been realised hitherto. Four family groups are involved, comprising 35 persons in all.

By the end of 1852 however, the pottery was owned and operated by James Williamson founder of the local oilcloth and floorcovering business empire.

A search of the local press for 1852 has failed to turn up any notice of sale for Scotforth pottery but something traumatic certainly occurred in the fortunes of the Bateson family in the autumn of that year. The Lancaster Gazette for Oct. 2nd and 9th carried a large notice of the imminent Auction sale of eleven lots of property and land in and around Burton-in-Lonsdale, all occupied and tenanted at that time by William, Richard and Thomas Bateson. Lot 2 Comprised “the dwelling house, late in the occupation of Widow Bateson also the valuable pot-kiln now occupied by Thomas Bateson and Ellen Hodgson, in a good state of repair and attached to the pottery a right of getting clay upon the valuable clay allotments”.

Williamson was already familiar, not only with the pottery industry of Burton-in-Lonsdale but more specifically, with the Bateson family. A Shrigley-Williamson Day Book for 1842-46 records regular sales of casks of red lead for making glaze to the brothers Thomas and Richard Bateson of the Potters Arms Pottery, Burton. It seems possible that the Batesons approached Williamson privately and offered Scotforth Pottery as an investment, probably at a cheap price for a quick sale, an offer likely to appeal to a man of Williamson’s business acumen. (Scotforth Pottery by V.G. Niven)

A crisis was definitely looming in the Bateson family as suggested in the above article, which could well have been the reason for William selling up Scotforth Pottery so quickly and returning back to Burton.

The Burton-in-Lonsdale sale in the autumn of 1852 was triggered by the death of William’s mother, Ellen Bateson. William’s father had died 10 years previously and his will stated that his estate should be put into trust with all rents and profits going to Ellen until her death, at which point the whole estate should be sold and (unequally) divided amongst his children.

On the death of Ellen, the trustees sold the estate for £1880 (equivalent of £317K today). The problem was that the trustees had (allegedly) mis-managed the estate funds over the 10 years since William’s father had died. The trustees had allowed some existing debts to go unpaid which had caused them to accumulate interest. According to a later court hearing, one of the debts was caused by William’s father not leaving enough funds in his personal account to bury him! The trustees and, surprisingly, their solicitor had also borrowed money themselves from the estate without accounting for it. This meant that, by the time all the estate’s debts had been deducted from the sale, there was only £278 (£47K in today’s money) left in the kitty. This was obviously of great concern to the beneficiaries.

Thomas Bateson, of Town End Pottery, one of the will’s trustees and William’s oldest brother, added to the crisis by going bankrupt in 1855 and being sent to debtors’ prison in Lancaster Castle. John Bateson of Bleaberry Pottery, William’s younger brother and the vandal of William’s clay pit a few years previously, aggrieved by the diminishment of the estate’s funds and, having obtained none of the legacy promised to him in the will, took all the trustees to court in 1858 in a brother versus brother and brother in laws trial. Julie has managed to obtain all the court documents and I have to say it does make fascinating reading. Regrettably the documents don’t though state who actually won the trial. The truth is though that they all probably lost in one way or another. Thomas remained, languishing in debtors prison, having lost Town End Pottery. The Potters Arms Inn and pottery were also sold, the owner being one of the trustees who may, I suspect, have stood surety for some of Thomas’s debts. Bleaberry Pottery went out of business and became semi derelict (John Bateson is later listed as being a gamekeeper in the 1861 census). Scotforth Pottery may well have been another casualty. Perhaps William needed to cash it in to help his family?

The Batesons accomplished a remarkable feat, taking what should have been a boon for the whole family and effectively turning it into a bust by means of financial mismanagement, court costs, solicitor fees and personal insolvency problems. You almost wonder if they were living beyond their means in the 1840s in anticipation of a large inheritance that failed to materialise. By the end of the decade I suspect that Bateson family Christmas get-togethers were somewhat muted affairs perhaps noted more by which family members were absent than those that were present.

Greta Pottery,by contrast, thrived during this period. Indeed the trials and tribulations of the Bateson family possibly helped Greta Pottery gain a more dominant position in the market for stoneware bottles, as the Batesons were probably more focussed on personal affairs than producing pots at this time.

I’m sure William would have been disappointed with the loss of Scotforth Pottery, as he must have invested a lot of money, time and organisation into it. I’m not sure what William did on his return to Burton. It’s likely that he just got a job as a thrower at one of the Burton potteries, but I don’t know which one. His occupation was a still “potter” on the 1861 census, however on the 1871 census his occupation is down as “Wooling Cloth Agent”.

Whilst William embarked on his Scotforth Pottery adventure, Matthew leased Greta Pottery to a local businessman, James Kilburn.

Matthew was having problems of his own in the 1850s. In 1851 he was living near Fleetwood where his occupation was “lodging house keeper”. Shortly after this he surprisingly moved to Belfast where he leased property on Corporation Street and ran a public house and a commercial boarding house. It seems Matthew had financial issues in Ireland, as his name appears in bankruptcy proceedings in the Dublin Gazette of 19th June 1855 and again the following day in the Bankrupt and Insolvent Calendar, Dublin, 18th June 1855 where it appears that he is in debtors’ prison (he would have been 73 years old)! He sold his land in Over Kellet around this time, presumably to alleviate his predicament and get him out of jail!

In 1857 Matthew once again tried to sell Greta Pottery:

TO BE SOLD BY AUCTION,

At the House of Mr. RICHARD BATESON, the Potter’s Arms Inn, in Burton-in-Lonsdale, on MONDAY, the 28th day of DECEMBER, 1857, at Six o’clock in the Evening, subject to such conditions as shall then be produced, all that

FREEHOLD POT KILN,

WITH all Rights, Privileges, and Appurtenances annexed thereto, situate at Burton-in-Lonsdale, in the West Riding of the County of York, formerly in the possession of Mr. Matthew Jackson Caton, (the Owner) and now occupied by Mr. James Kilburn, as Tenant thereof.

The Property is distant about two miles from Bentham, where there is a Station on the Skipton and Lancaster Branch of the North Western Railway; and the extension Line from Ingleton to the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway, now about to be constructed, will tend greatly to facilitate the transmission of the Pottery Ware of Burton.

Further particulars may be had on application to Mr. Caton, or at the Offices of Mr. EASTHAM, Solicitor, Kirkby Lonsdale.

Kirkby Lonsdale, 8th December, 1857,

(Lancaster Guardian, 8th Dec, 1857)

Once again it didn’t sell. Indeed Matthew was still the owner in 1860 whilst living in Belfast (electoral register).

In 1861, Matthew moved to 8 Queens Terrace, Fleetwood, one of the area’s premier addresses!

Matthew remained here until his death on 16th January 1863 at the age of 80. His occupation on his death certificate is, surprisingly, farmer!

Interestingly, Fleetwood Museum recently bought 8 Queens Terrace (2022) and is planning to incorporate it into the Museum, which is next door (6-7). They intend to make it into a “display home which would allow visitors to get a fascinating view of life through the ages for those who lived there”. I look forward to visiting it.

I suspect Greta Pottery was sold to James Kilburn a short time after Matthew’s death in 1863 and probably at a bargain price.

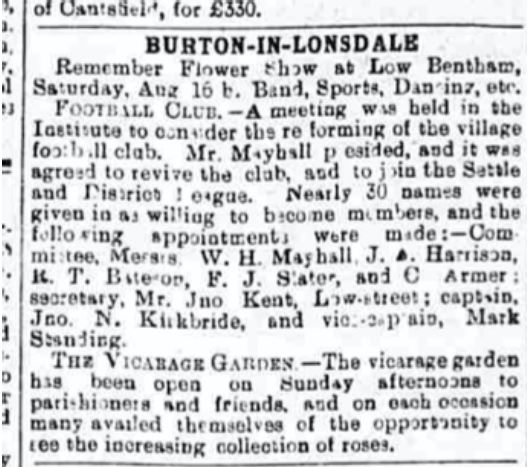

James Kilburn (1792- 1878) – ran Greta Pottery c1850-1878

James Kilburn bought Greta Pottery in 1863 from the estate of Matthew Jackson Caton after renting it from around 1850.

I had always thought that James Kilburn was a Burton potter who’d served an apprenticeship at one of the Burton potteries prior to running and buying Greta Pottery. Research though seems to indicate that James was not a potter at all, but a business man and came from the emerging Victorian middle class. This in itself was unusual for a Burton pottery, where the owner was usually the main thrower in the thick of it in the pottery workshop. The problem with running a pottery from the potter’s wheel is (and I can testify to this) that it has a habit of consuming all your time so the manufacturing becomes everything. This can then prevent you from seeing the whole picture clearly in terms of market demand, cash flow, what makes the most profit and significant changes within the pottery industry. Now this isn’t a huge problem if you are self-employed, as the only person to take the hit is the fool on the wheel. However if like the Burton potters, you are employing upwards of eight people whilst sitting on the pottery wheel with your foot “off the pedals” with what is actually happening with the business, then you have a problem. I feel that a businessman freed from the workshop is in a better position to see this “bigger picture” and make more informed choices for future continuity. The long term future of an industrial pottery in Burton probably relied more on good business men than it did on good potters. I feel James Kilburn was first and foremost a good business man.

James’s father, Kenard, came from relatively humble beginnings working as a coal digger (parish records). However he obviously had a flair for commerce and very effectively managed to pull himself up by his own bootstraps, starting numerous successful businesses, gaining a reputation as “an honest and upright man” (Manchester Courier 1840) and moving up the social classes. In the 1822 Baines directory Kenard is listed as:

Kilburn Kenard and Sons, rope twine mfrs. Drapers, grocers, iron-mongers and tallow chandler

Kenard’s death was reported in national newspapers when he passed away at the ripe old age of 92 in 1840 which would have been seen as very old in the 19th century. James inherited the tallow chandlery (posh name for a candle making shop) and the grocers from his father. James must have also inherited his dad’s eye for a good business opportunity, as when Greta Pottery came up for rent, he was quick to take it on.

James experienced a problem with one of his employees, in the early days of running Greta Pottery:

HORNBY PETIT SESSIONS…. Absconding from Service.- John Savage was charged with absconding from the service of his master, Mr James Kilburn of the Pottery, Burton-in-Lonsdale. The case was fully proved, and Savage was committed to the House of Correction at Wakefield for one month. (Lancaster Gazette 12 June 1852)

My first instinct was that the employee in question was most likely a young apprentice. However research has shown that John Savage was an “earthenware potter”. He would have been 31 years old at the time that he absconded from Kilburn’s employment. He had a young family, so it must have been hard for his family when he was sent to prison in Wakefield. The Savages were not a Burton family but originally from Derbyshire and Bradford. This incident was possibly no bad thing for James, as it would have certainly kept his remaining work force on their toes. James was clearly not a man to mess with!

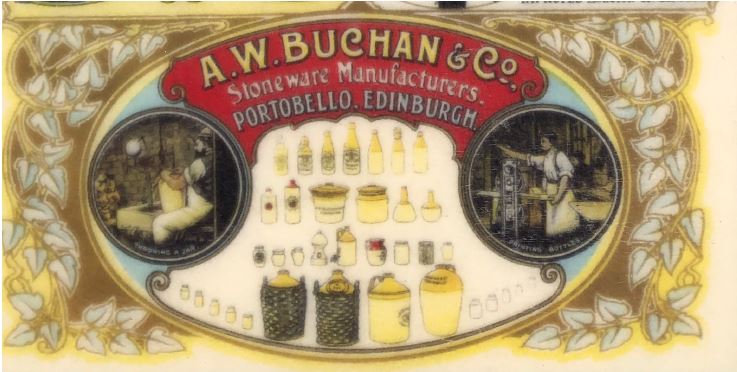

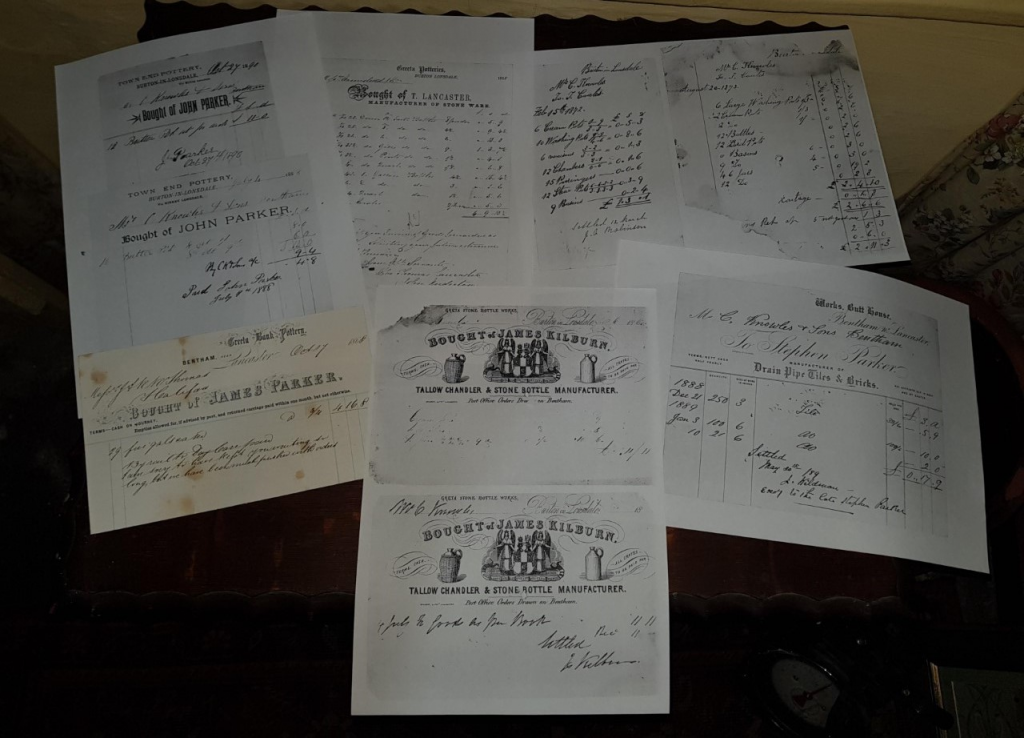

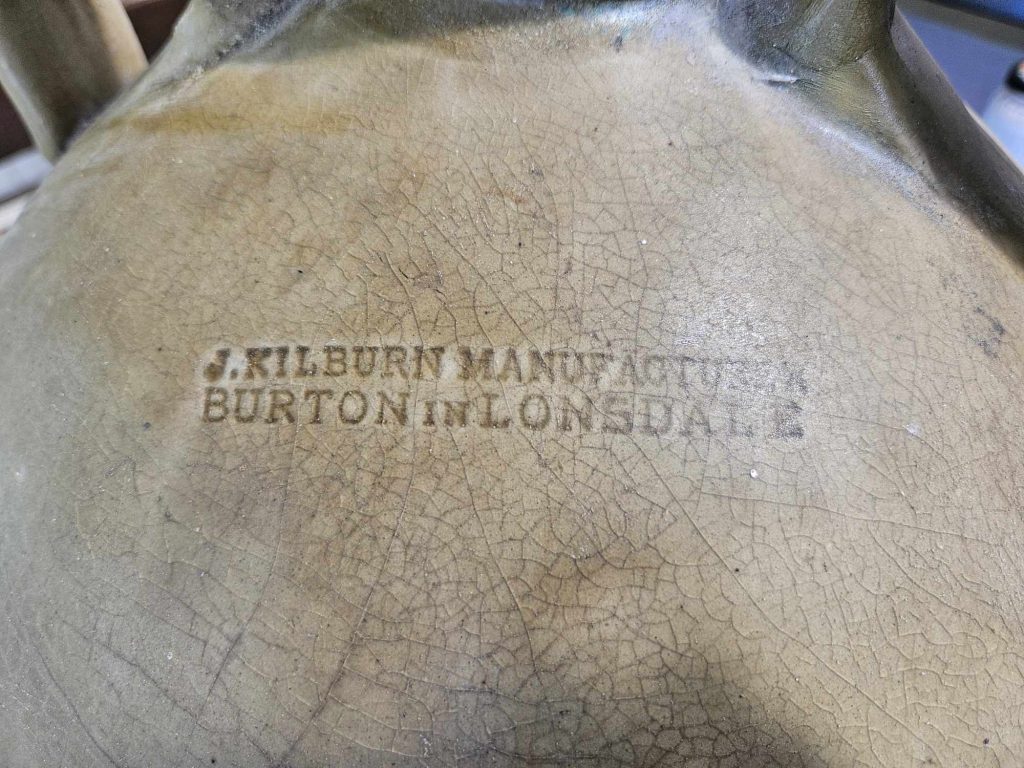

James seems to have had a good understand of branding and advertising. His

letterheads certainly look very slick and professional. James named the business “The Greta Bottle Works” and he had his name stamped on the shoulder of each bottle. James was unique in being the only Burton potter to stamp his wares and I’m sure this “free” advertising brought in more business for him. It certainly makes the bottles more valuable to collectors of Burton pottery as there can be no doubt of their origin. I have known the larger Kilburn bottles (4 gallon to 6 gallon) fetch upwards of £500 to £800 at auction. I have often wondered what James would have thought of his pots being worth that amount! If you’re ever looking at old stoneware bottles in an antique or bric-a-brac shop, then watch out for “J.Kilburn, manufacturer, Burton-in-Lonsdale” usually stamped on the shoulder. You may grab yourself a bargain. I recently picked up a 2 gallon Kilburn bottle for £14 (eBay 2023).

Trade must have been going well for James, as he was able to expand the business and buy Wilson’s Pottery located on the opposite side of the road to Greta Pottery. The previous occupant of Wilson’s Pottery, George Wilson, was married to William Bateson’s sister Agnes. George had been declared bankrupt in 1842 and spent some time in debtor’s prison in York Castle, which I’m finding is not an uncommon thing for a Burton potter! I’m not certain if George managed to resolve his bankruptcy problem or if his pottery was entrusted to his creditors, either way James Kilburn bought it.

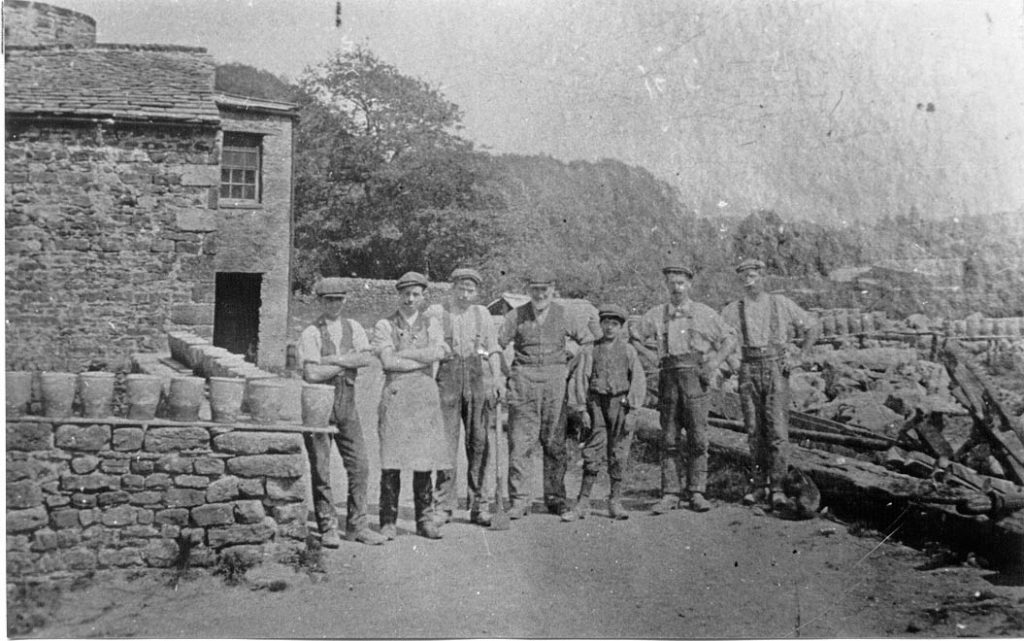

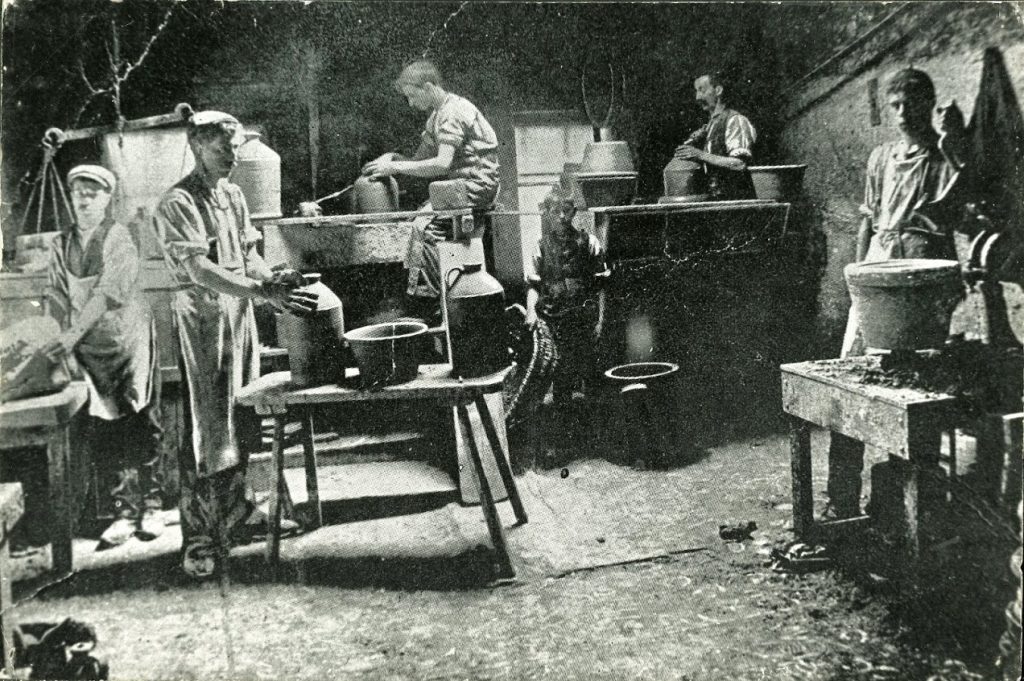

It’s hard to speculate as to what the scale of the operation was at Greta Pottery under James Kilburn’s ownership. I would guess at its peak that it would have employed at least 20 workers including some boys. This is based upon the fact that I know Waterside Pottery, Burton-in-Lonsdale, employed around 30 men in 1906 and had three kilns, whereas Greta Pottery had only two kilns. If the Greta Pottery kilns were a similar size to the Waterside Pottery kilns and they were firing them every week then they would have been producing 2400 one gallon bottles or their equivalent per week. This weekly routine would also involve digging and processing around 12 tons of clay and carting and shovelling 24 tons of coal into the kilns. It would have been one hell of an operation and I think during this period Greta Pottery would have been deemed as the most important pottery in the village. Looking at the former site of Greta Pottery today, it is difficult to imagine that this ever happened here.

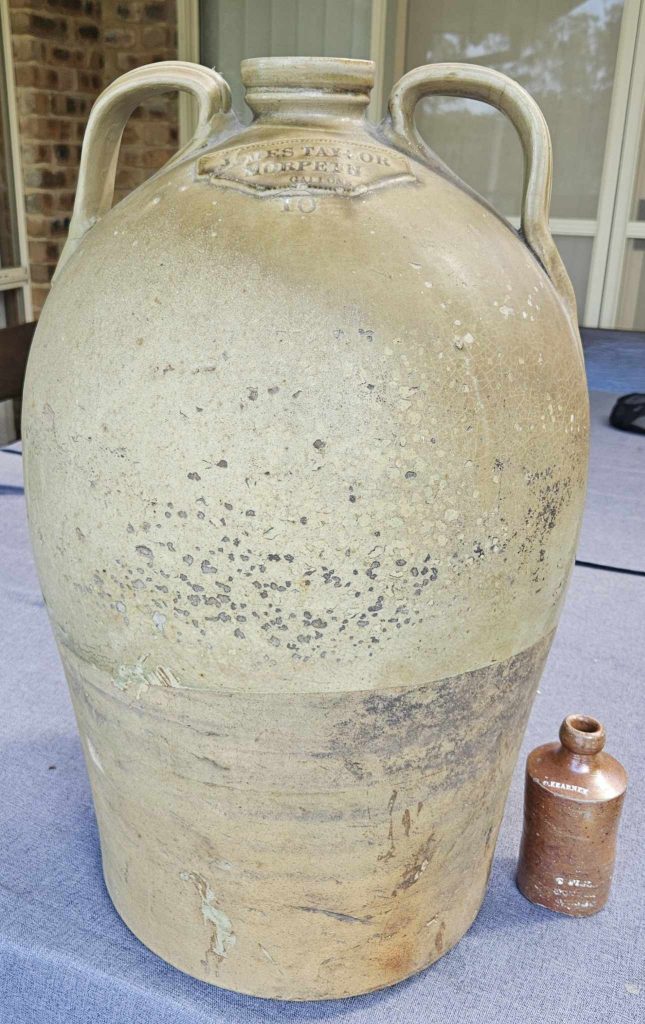

Kilburn bottles were sold not only all over the UK but also exported around the world. The two gallon bottle pictured below was made for a spirit merchant in Morpeth, Australia and currently resides in Morpeth Museum, New South Wales.

It gets better! Unprompted, whilst browsing her phone one lunch time, my wife stumbled upon an Australian bottle collectors’ site. I contacted them (australianclaybottles.com) asking if they had any Kilburn bottles. I got a swift response from a chap called Mark, saying that, although he didn’t have any, a friend of his, Dave, had a 10 gallon Kilburn bottle with a “James Taylor, Morpeth” stamp. I misread this to begin with thinking that his friend had 10 one gallon bottles. I reread it and the truth dawned on me. Mark said he’d ask Dave to send me a photograph.

The Bateson family had mentioned to me when I interviewed them in the 1980s that occasionally 10 gallon bottles were made at potteries in Burton. To be honest I really dismissed this as being the exaggerated memories of old men looking back in time with rose tinted spectacles. I have certainly never seen a Burton 10 gallon bottle before in any museum or private collection. I’d always assumed that the largest Burton bottle was the 6 gallon bottle and the 10 gallon bottle was the stuff of myths and legends. The capacity of a 10 gallon bottle would be 60 standard bottles of wine. It is difficult to imagine how hard it would be to lift such a bottle once full.

I know that a 6 gallon bottle was made from a 66lb ball of clay, which is an impressive amount of clay to handle, this would mean that a 10 gallon bottle would require 110 lbs of clay, which is a seemingly impossible amount of clay to deal with on a pottery wheel (the largest pot at Bentham Pottery, a biscuit barrel requires a measly 5lbs of clay). To give this some scale, 110 lbs is 7.9 stone – about the average weight of a 13 year old child. I convinced myself that Dave was probably mistaken but I waited eagerly for the photographs.

The photographs came back. I was wrong. Dave genuinely has a Kilburn 10 gallon bottle. It even has ‘10 gallons’ stamped on it. Not only that, but its condition is excellent, both handles being intact. This is a very rare Burton pot and one I never expected to see. In all honesty I am truly humbled by its very existence. The skill required to throw such a large bottle; handle it through the glazing (the pots were fired only once – there was no bisque firing so the potters were applying glaze to an unfired and hence much more fragile pot); fire the kiln at a slow enough rate to prevent thermal shock (to which larger pots are more prone) and then, to top it all, transport it by horse and cart to Bentham, railway to Liverpool, ship to Sydney and finally river steamer to Morpeth, Australia without it breaking is completely beyond me. I will never again complain about having to take a car chock-full of pots to a local craft fair.

And you really have to marvel at how such a large and rare bottle, which at the very least has to be 156 years old, has survived to the present day and then comes to light not in the vicinity of its hometown, Burton-in-Lonsdale, but on the other side of the world! Dave kindly sent me a number of photos and here they are:

It’s very likely that James Kilburn installed the first steam engine at Greta Pottery, I just don’t know for certain if he did. There is no mention of a steam engine on the 1860 advert for the sale of Greta Pottery (and I feel certain that it would have been mentioned). It is hard to believe that he could have exported 10 gallon bottles to Australia without some mechanisation of the process!

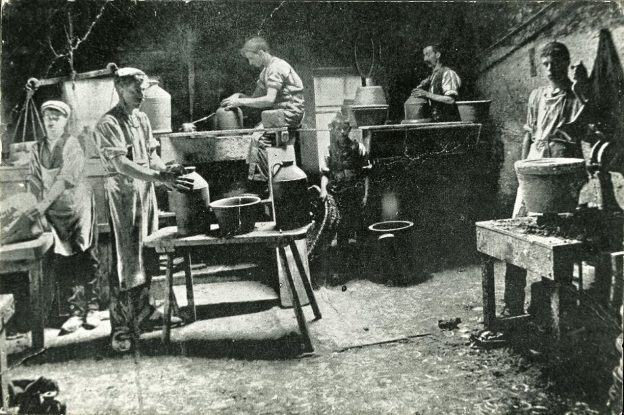

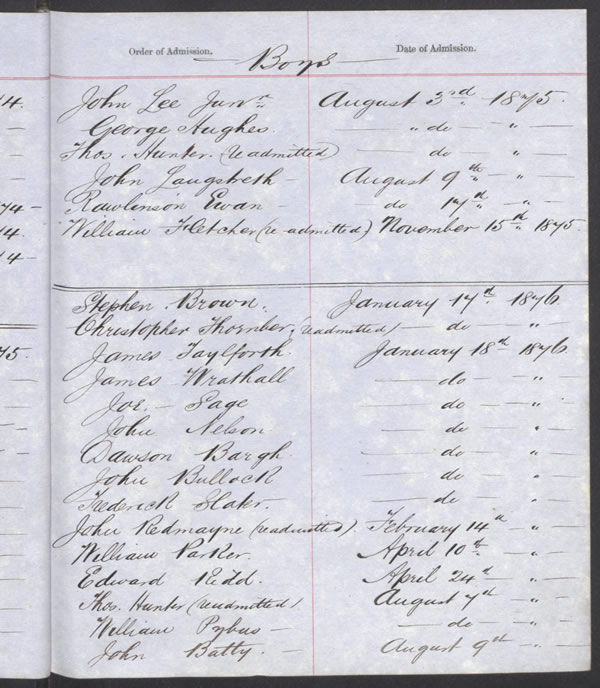

The Burton potteries were late to join the steam age, leaving it until the latter part of the 19th century. Prior to steam power everything in the pottery industry was done by hand. The pottery wheels were powered by boys, usually the sons of the potters sitting opposite the thrower and turning a hand crank to rotate the wheel. They were able to vary the speed by turning the crank faster or slower, usually accompanied by shouts from the thrower! The clay would have been mixed and prepared by hand, which would have been incredibly hard work and time consuming, a task that a steam engine would have made light work of.

Josiah Wedgewood, the famous Stoke potter was an early adopter of steam. All the wheels and machinery at his Etruria factory were steam powered by 1800 and other Stoke potteries followed closely behind him. Why then you might ask did it take the Burton potters so long to join this industrial revolution. The reasons are possibly that steam engines were very expensive to install for relatively small potteries and Burton was a little remote from industrial heartlands and engineering works. Added to this was the fact the potters had big families with plenty of boys that had no choice but to work for their families on low to zero wages possibly aided by relatively lax laws on child labour. It wasn’t until 1893 that a law was passed setting a minimum age of 11 for the employment of children in the pottery industry.

You could argue that this lag behind industrial developments was a contributing factor to the eventual demise of the pottery industry in Burton.

James Kilburn worked Greta Pottery for around 30 years until his death in 1878. James’s last will and testament reveals that he died property rich, owning two potteries, one candle shop, eight cottages (with tenants), various plots of local land together with his own house.

James’s son, William Kenard Kilburn inherited the pottery. William had in truth been running Greta Pottery alongside his father for some time and so had a good understanding of the business. Tragically though, William outlived his father by a mere three months, dying from acute rheumatism and pericarditis at the young age of 41 years, so this succession sadly had no longevity. If William had lived and possessed the same business acumen as his father and grandfather then who knows where he might have taken the business?

The Kilburn Estate put the pottery on the market and it was sold to Thomas Coates of the Baggaley Pottery, located conveniently just on the other side of the road from Greta Pottery.

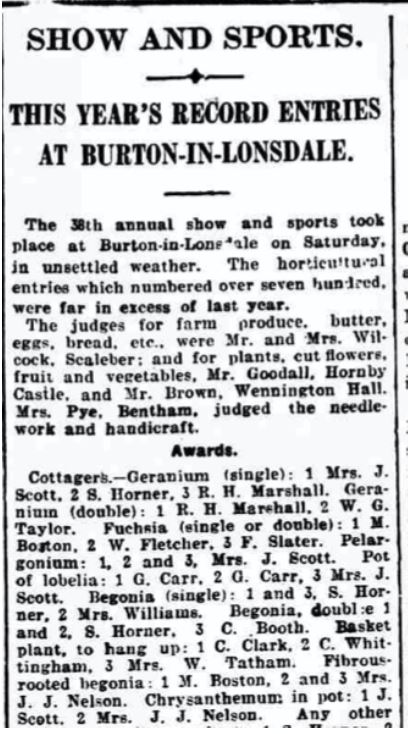

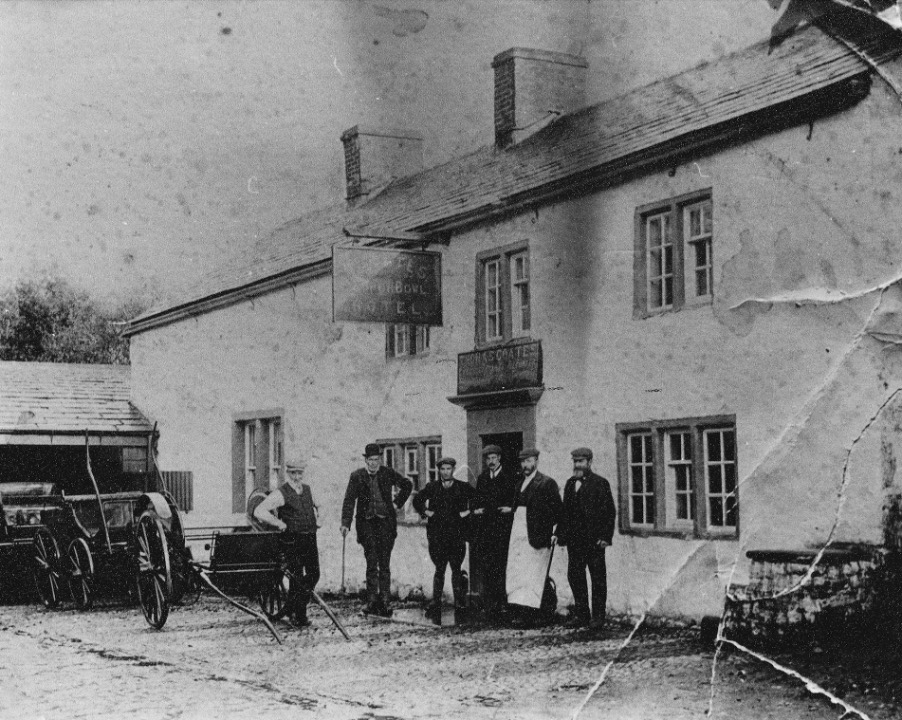

Thomas Coates (1845-1923) – ran Greta Pottery 1879-1906

Thomas Coates was a good potter and an astute businessman. I’m guessing he was aware of market trends and was desperate to get onto the stoneware bottle bandwagon. It’s possible that prior to the purchase of Greta Pottery Thomas had no access to any stoneware clay in Burton. The Baggaley Pottery kilns certainly wouldn’t have been able to fire to stoneware temperatures. Buying Greta Pottery opened up the stoneware door for him. Thomas no doubt managed to retain Greta Pottery’s customer base and orders. Thomas thus began manufacturing stoneware bottles on one side of Burton Hill Road and traditional country pottery on the other side.

In addition to running Baggaley Pottery, Thomas Coates was also the landlord of the Punch Bowl Inn, continuing a long line of combined potter/publican in the village. Rumour has it that he paid his workers on a Friday night over the bar of the Punch Bowl.

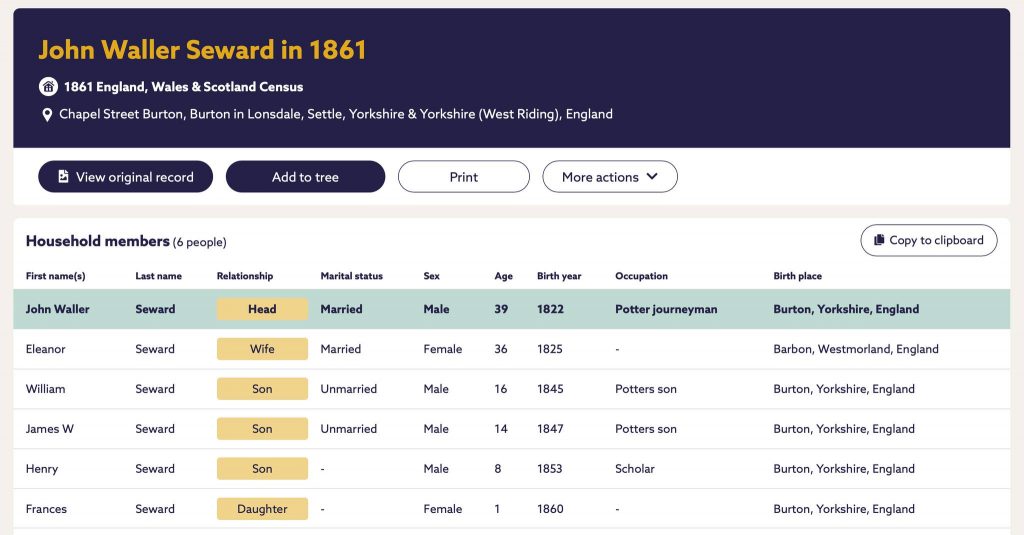

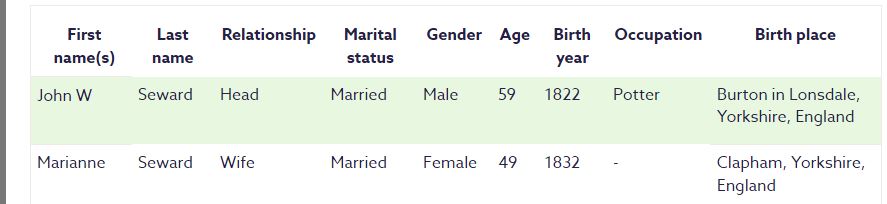

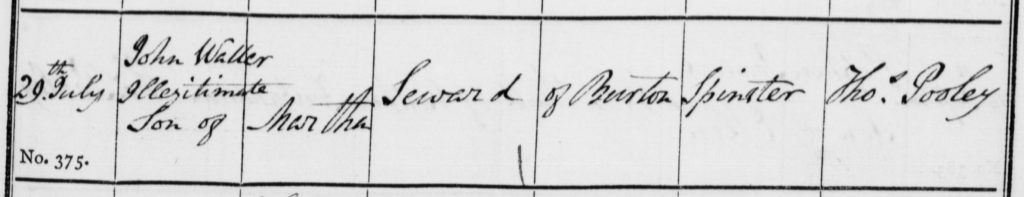

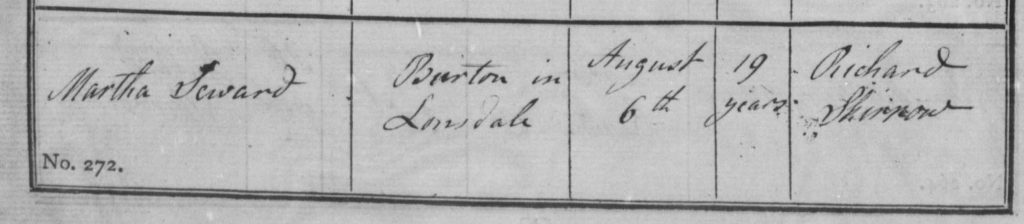

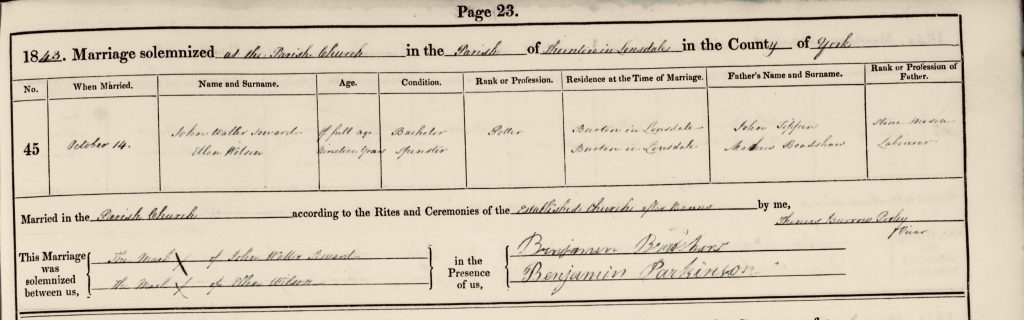

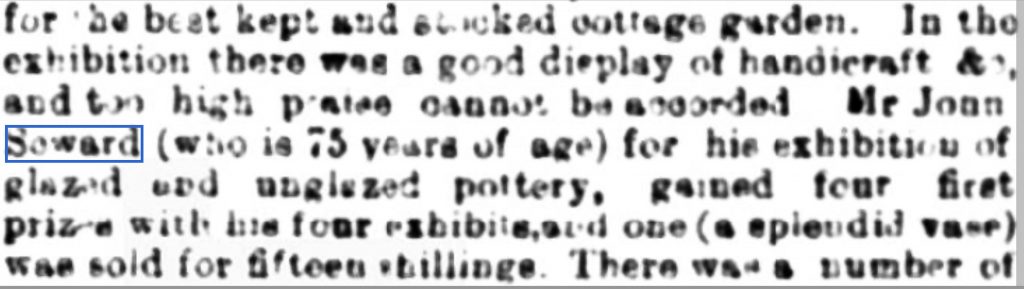

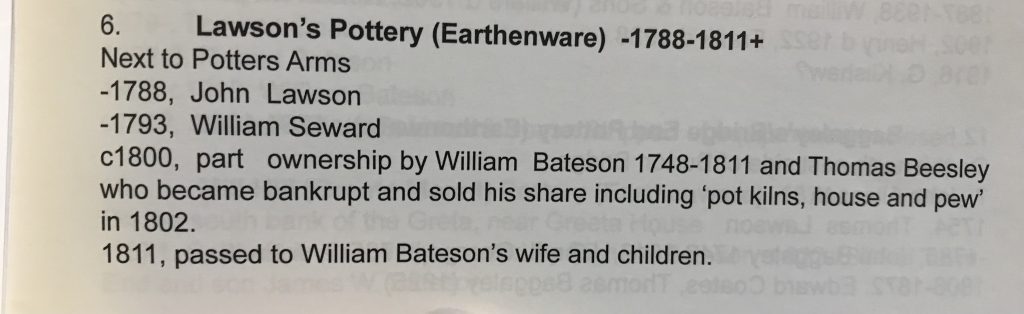

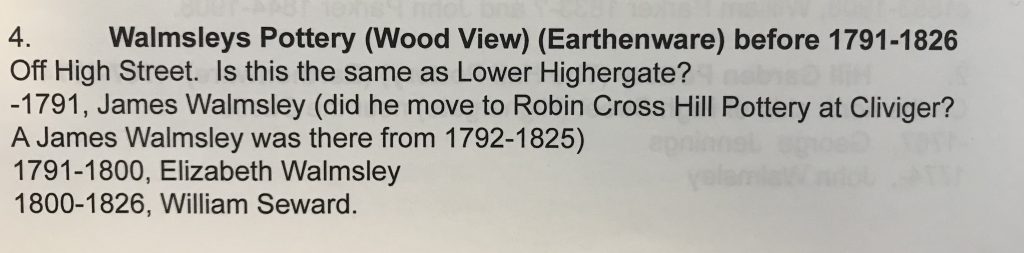

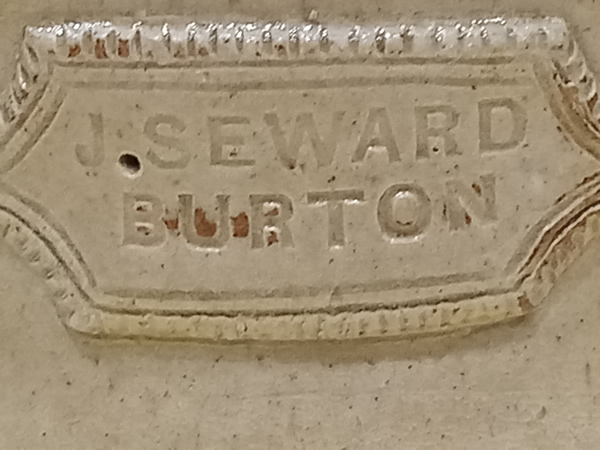

Thomas diversified towards the end of the century and together with one of his workers, John Seward, began manufacturing art pottery, possibly inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement. These stoneware pots were typically decorated with sprigs (press moulded casts from plaster of Paris moulds), some fine examples of which can be found in the Folly Museum at Settle, including a particularly grand water filter made for the Craven Heifer at Ingleton and actually signed – “J.Seward, Burton”. Coates and Seward took these pots to sell at Victorian bazaars, which I can imagine were akin to a modern day craft fair. This was an interesting direction for the Burton pottery industry to take and could potentially have had long term benefits in ensuring the continuity of the pottery industry in Burton. Moorcroft Pottery in Stoke-on-Trent went down the Art pottery route and they are still in business today.

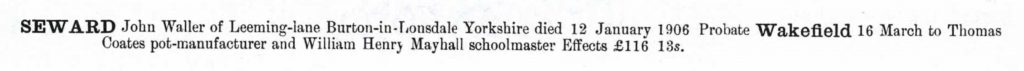

Thomas together with his sons, Jack and Edward carried on producing stoneware at Greta Pottery for 23 years until 1902 when he sold Greta Pottery to Robert Bateson formerly of Waterside Pottery.

Robert Bateson (1855-1908) – ran Greta Pottery 1906-1908

Robert Bateson was one of three brothers that ran Waterside Pottery in Burton. Robert unfortunately fell out with his brothers as he didn’t think that the business was moving in the right direction with regard to products and manufacturing techniques. He wanted to “modernise” the Burton pottery industry and his brothers were having none of it. He sold his share of Waterside Pottery to his brothers and with the proceeds bought Greta Pottery in 1906.

Robert began introducing up-to-date equipment into Greta Pottery and for a time the future of the Burton pottery industry could well have laid in the hands of Robert Bateson and Greta Pottery; however Robert’s dreams and aspirations were never realised due to his untimely death in 1908 at the age of 53. Prior to the First World War the pottery owners needed to be making the right decisions and investments in order to guarantee the long term future of the pottery industry in Burton. It is very possible that Robert Bateson was one of the men that had the potential to do this. I’m sure Robert questioned his decision to leave the partnership with his brothers, particularly as Waterside Pottery really boomed prior to the First World War, but Robert never lived to see the decline in trade in the 1920s due to a reliance on traditional techniques and a tunnel vision with regard to the products they were making. Stoneware bottles were slowly being usurped by the glass bottle and the Burton potters turned a blind eye to this fact.

In his will, Robert Bateson left everything to his wife, Sarah. Sarah then tragically died from a heart attack, aged 51, just one year after Robert in 1909. Sarah made provision for all five of her sons in her will and stipulated that two of her sons, William and Ernest, who already worked at Greta Pottery, should be allowed to manage and carry on Greta Pottery and be paid wages until such a time as her trustees sell and dispose of Greta Pottery.

William and Ernest continued with Greta Pottery until 1910 when it was sold to Waterside Pottery. I suspect that William and Ernest could possibly have continued running Greta Pottery if they had a strong desire to (at the discretion of the appointed trustees and other brothers). They could have potentially bought out their other brothers or brought them into a partnership, after all, the stoneware bottle market at this time was still vibrant. In fairness though, they probably inherited the pottery when they were a bit too young to run it: William would have been 24 and Ernest just 18. Also after having lost both parents very suddenly they may have wanted a clean break from Burton and potteries. I’m not sure what William did, but Ernest and his brother Richard left for Australia in 1910 on assisted passage aboard the SS Marathon. Ernest’s occupation on the ship’s record was pot maker, Richard, joiner. Ernest settled in Queensland, Richard in NSW.

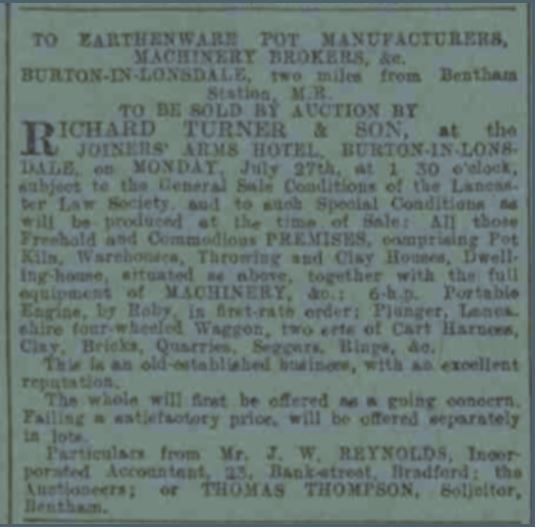

BURTON-IN-LONSDALE, YORKSHIRE.

SALE OF A VALUABLE FREEHOLD POTTERY AND BUSINESS, AND A DWELLING HOUSE.

TO EARTHENWARE POTTERY MANUFACTURERS AND OTHERS.

TO BE SOLD BY AUCTION, BY R. TURNER & SON,

AT THE PUNCH BOWL HOTEL, BURTON-IN-LONSDALE,

ON THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 9th, 1909, At Six o’clock in the Evening prompt, Subject to the General Conditions of the Lancaster Law Society, and to such special conditions and in such Lot or Lots as may be determined upon at the time of Sale,

Lot 1.-ALL those Old-established, Valuable, POTTERY WORKS. Known as THE GRETA POTTERY COMPANY,

Situated in the Township of Burton-in-Lonsdale, in the West Riding of the County of York, Containing Circular Pot Kiln with all the necessary Quarrel and Bricks, Engine Horse, Throwing House, Press House, Drying Rooms, Warehouses and Yards thereto belonging. Also all the recently-erected and modern Machinery as fixed in the Works, consisting of Horizontal Engine (12 h.p.) by G. F. Riley, Huddersfield; Vertical Boiler. Donkey Pump, Blunger, Press and Pump, Pug. Two Throwing Wheels, Dish and Bottle-making Machines, Six Mould Castings, all the Shafting and Pulleys connected therewith, and other necessary Machines and Tools used in the trade of a manufacturer of Jars and Dishes.

The property is sold as a going concern and the Stock-in-trade at the time of completion of the purchase shall be taken by the Purchaser at a valuation according to the Conditions of Sale.

The benefit of a Licence to take Clay from and under a Field known as Bleaberry Hill, up to August 1st, 1911, at a yearly rental of £10, is also included in the purchase.

Lot 2. All that Valuable DWELLING HOUSE, situated in Chapel Lane, Burton-in- Lonsdale, containing Dining Room, Drawing Room, Kitchen, Pantry, 4 Bedrooms, Wash- house, the usual Conveniences and Garden to the rear.

Both Lots are in the occupation of the Executors of the late Mrs. S. J. Bateson, and immediate possession may be had if desired.

Each lot forms a highly desirable investment. The late Mr. Robert Bateson was connected with the Pottery trade for some 10 years. He acquired Lot 1 in 1906, previous to which time the business had been carried on for many years, and built up a large connection.

Further particulars may be had on application to the Auctioneers, Bentham: or to MESSRS. JOHNSON & TILLY,

Solicitors, Lancaster. (The Westmorland Gazette. September 4th, 1909)

The pottery was then stripped of all its machinery which was taken to Waterside Pottery and the building was sold to Wilfred Waggett on the condition that it would never again be used for manufacturing pottery. Wilfred Waggett kept his word on this and the building was used for trading horses and as a knackers yard. The Greta Pottery site seems to have always attracted larger than life characters and I hear that the Waggett family certainly carried on this tradition albeit not as potters.

The building was eventually converted into houses in 1978 and is now 1-5 Greta Heath. Jack Brayshaw, himself a descendent of Burton potters was one of the builders working on the site of Greta Pottery. I discussed this with him via Facebook:

“Bill Waggett owned Greta Pottery in the seventies, I worked for Mick West and Pete Keenan, we took the old building down where the kiln was. The other one was turned into four cottages, when we dug out for the septic tank we found dozens of clay bottles, they sold for £1 pound each, that was a good deal then.”

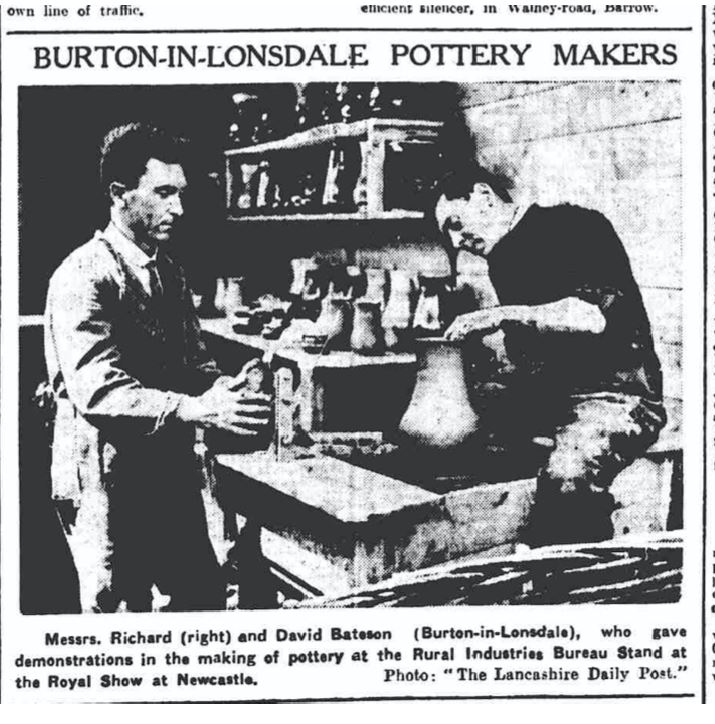

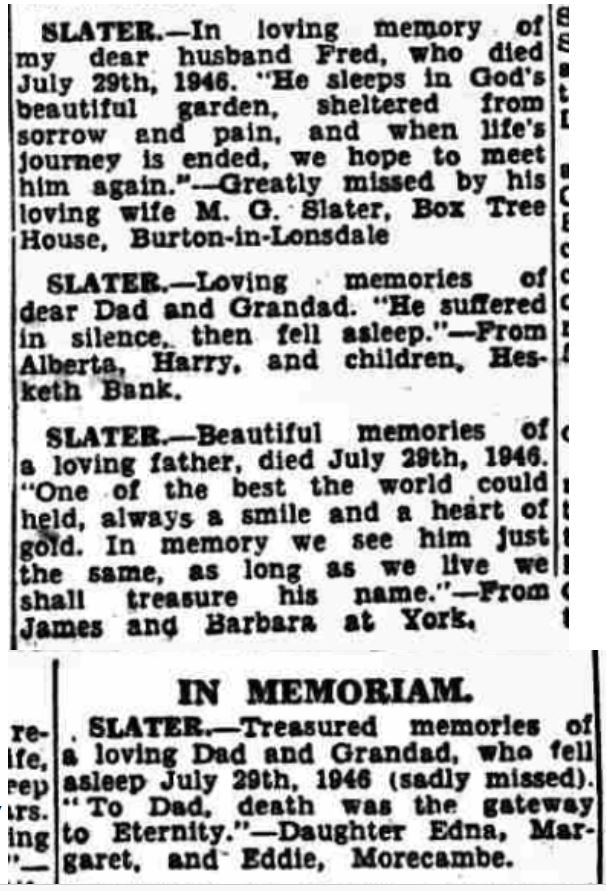

William’s Sons – James Bateson (1835-1915) and Richard Bateson (1836-1925) – both worked at Greta Pottery

I can’t leave the story of Greta Pottery without mentioning the sons of William Bateson, the man who started Greta Pottery in the 1830s: James and Richard.

James and Richard worked for their father as youngsters both at Greta Pottery and Scotforth Pottery. Richard then went to work for his cousin at Eccleshill Pottery, Darwen before returning to Burton to work at Waterside Pottery. James worked at both Greta Pottery and Waterside Pottery. I suspect that James was one of the main throwers under Kilburn’s ownership of Greta Pottery. Both men became highly skilled potters.

James and Richard are mentioned in the Dalesman article of 1949:

“Preserve us from Trade-Unionism and internal broil,” was the public prayer of master-potter James Bateson, an honest godly man and a local preacher, still remembered”

“His sons James and Richard were strict tee-totallers. Richard worked mainly at Waterside. He lived to a good old age, and is remembered as a lovable man, called affectionately ‘Uncle Dick’- a skilled craftsman, maker of many ornamental garden pots to be seen in local gardens.” (Dalesman magazine 1949)

I can’t help wondering if the fact that James and Richard were strict “tee-totallers” was due to the antics of the Ancient Royal Fissers Club. Perhaps they’d witnessed the hanging of one of its members?

Richard Timperley Bateson, or RTB for short, the very last Burton potter and the subject of a recent book of mine remembers James and Richard (distant older relatives of his) very fondly, as they used to come into Waterside Pottery on occasions, after they had retired, to throw pots. RTB can remember, with some degree of shame, dripping engine oil onto James’ cap through the floorboards on the second floor whilst James was throwing downstairs. RTB always spoke with a high degree of reverence about Richard:

“I wish I could have carried on in the way Richard Bateson did. He was one of the cleverest potters that I think this village has ever had in terms of colours, ideas, decoration and experiments. It’s a pity that he couldn’t have had a free hand. He was no business man in any shape or form, but he was just an artist, a pottery artist and a country pottery artist too. A man full of inventiveness. Wonderful chap.”

When you consider that RTB went on to teach at some of the most prestigious art colleges in the country, you have to take his opinion on this seriously. I have yet to find a Burton pot that can be attributed directly to Richard Bateson. It is very possible that Richard never signed his pots. I am hopeful that one day a Richard Bateson pot will come to light.

Conclusion

Before writing this article I had never really fully appreciated the significance of Greta Pottery within Burton-in-Lonsdale. Greta Pottery effectively pioneered the production of stoneware in the area and I think that its success was the inspiration for building Greta Bank Pottery and Bleaberry/Waterside Pottery (both stoneware potteries predominantly making stoneware bottles).

I can’t help but be impressed with the array of talents that Greta Pottery attracted: the risk taker and visionary William Bateson: the investor Matthew Jackson Caton; the business man James Kilburn; the business man and potter (a truly rare combination of talents) Thomas Coates; the moderniser Robert Bateson; the artists Richard Bateson and John Seward; and a whole host of unsung yet talented pottery workers making the products. Would the pottery industry in Burton still be around today if these men had been in charge in the industry’s declining decades of the 1920s and 1930s? Possibly. Sadly we will never know and so we are left with a pottery village with at least 300 years of the tradition bereft of a single pottery.

Lee Cartledge, Bentham Pottery, 2024

Appendix

Writing essays on the Burton potteries and publishing them in my blog has meant that I am occasionally contacted by descendants of the potters.

Whilst writing this essay I am delighted to say that two of the great granddaughters of Robert Bateson emailed me: Vera Read and Karen Swindle both Australian and living in New South Wales. Vera had actually previously visited me at Bentham Pottery in August 2011, whilst visiting the UK, and, in particular, the pottery village where her family came from. Vera kindly allowed me to use the family portrait of Robert Bateson in this essay.

I left their grandfather Richard Bateson in the above essay heading out to Australia with his brother Ernest in 1910 on assisted passage aboard the SS Marathon, having just lost their parents and sold Greta Pottery. Here is a bit of the correspondence with these descendants:

I believe Richard went to the gold fields near Bendigo and Ballarat Victoria panning for gold and doing any work he could find? Even some pottery as that area is renowned for its pottery in Australia. He joined the Assembly of God’s Church and I think it was with the church he travelled to NSW helping build new churches and doing farm work. He brought a small property at Mandagery (near Parkes) and made a living cutting timber and selling charcoal. He lived a quiet life not venturing far from the farm as I remember.

He played the piano most afternoons, usually hymns but I was too silly to learn from him. Something I now regret. He built his home and sheds and helped others in the area with their building projects as well as helping on farms to make money for his family. A keen reader and always interested in the news of the day. He encouraged all of us grandchildren with our education and to find a job we loved and to do it well. Unfortunately I know nothing of Ernest’s life or family but as a child, when we went on holidays, Dad would check the phone book of the area but never found any Batesons listed as Granddad never talked much about his family only to say they lived in Yorkshire, England. (Karen Swindle)

Richard travelled around NSW mainly up the North Coast before settling around Parkes where he married Ethma. There were 5 children. My grandfather never seemed to want to talk much about his early life, or maybe we didn’t ask enough questions. I guess it was a time when questions were not asked so freely as today. (Vera Read)

Richard lived a long life and died in 1976. He had 5 children. There are now 12 grandchildren, 37 great grandchildren and Vera has yet to work out how many great great grandchildren! Vera recently discovered that Ernest settled in Queensland, married and had one son called Ernest Richard Bateson.